Five Points, Vol. 6 No. 3

Fall 2002From Barry Hannah, “So much of writing is hard work, but you don’t want to admit that when you’re younger because you just want to be a flashing talent and be god-struck.”

Sample Content

Pam Durban

Rowing to Darien

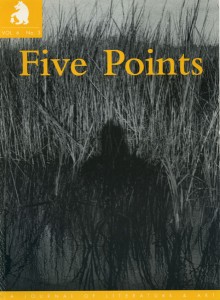

March 1839, just after midnight on the Altamaha River, and it’s cold, the thin, watery cold of spring on the coast of Georgia. Fluky breezes blow, smelling of silt and fish and woodsmoke. The hoot of a horned owl carries across the water, a heron’s croak, the creak of oarlocks and the splash of oars. The moon is up, one night past full; it throws a bright track on the water and across this track, Frances Butler rows a boat with a lantern set on the thwart. Out under the moon which lights up the whole sky, the lantern flame looks small, a small brightness crossing the river to safety. That’s how she thinks of it as she rows—a mission, not a flight—to dignify the journey and to keep the fear at bay.

Fear of the river to begin with. The Altamaha only looks slow because it is wide and deep, coiling through the Georgia swamps. But the Altamaha is a tidal river; the whole river moves as the tide pushes inland for twenty miles, then flows out again. On a tidal river, lacking strength and will, you go where the water goes which is—it occurs to her now as she rows away from her husband’s rice swamp—what Mr. Butler expected of her once they were marries. He the river and she the boat, carried on his tide. Whither thou goest; wives be subject to your husbands and all the other trappings of this world in which she has found herself, down here in the dark pockets of his wealth, the flood and drain of profitable estuary.

Now, as her husband’s boatmen have taught her to do, she sweeps the oars back, dips them deep, pulls with all her strength, all of this done quickly, for in the pause between strokes, when the oars are lifted, she feels the current grab the boat and pull it downriver. She is an accomplished horsewoman, a hiker in the Swiss Alps; she is no flower, but this is hard, nearly desperate, work. The sleeves of her dress are pushed up over her elbows; her hair straggles out of its twist. She rows steadily away, but someone rowing a boar across a river has to face the shore she’s leaving. One last trial, she thinks and would have laughed if she’d found the breath for it: to watch the scene of her downfall dwindle as disappear, though in this endless flat landscape that might take all night. So be it, she thinks, because once Butler Island is out of sight, she will be free. It is only a matter of time.