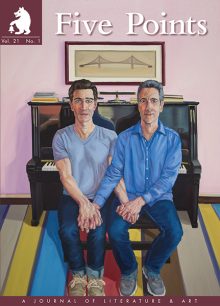

Five Points, Vol. 21, no. 1

Sample Content

Lauren K. Watel

Manners for Poets

Ah, poets. What a quirky, intelligent tribe. I’ve spent years among them, largely to my edification and delight. How marvelous they are, these tirelessly profound, studious word-crafters. Never dull, never predictable, they come in many models, and with a wide array of appealing features to choose from: monstrous erudition; groovy new-agey vibes; mad charisma; social clumsiness; bold fashion choices ranging from hipster chic to blazer-with-elbow-patches tragic; cutting wit; Sibylline inscrutability; blind devotion to even the most ne’er-do-well friends; sluttish disregard for former allies; childlike self-absorption; limited insight from decades of psychoanalysis; timidity; tendency to tantrums; tenderheartedness.

Given their myriad charms poets should rightly hold a place of reverence in the wider culture. However, the readership for this delicate art, at least in our great country, is miniscule, job prospects few and far between, recognition hazy, if at all, and glory fleeting. In light of these sad facts, the average poet’s allegiances to, and endless battles over, literary territory smaller than a window box seem all the more heroic. Not to mention the long days, years even, of sweaty struggle over every comma, every enjambment—all this effort culminating in a slender-spined paperback, sales of which might number in the triple digits. And that’s if you’re lucky. Naturally these noble, marginalized misfits are unconventional to the bone, dwelling as they do in uncertainties, mysteries and doubts, not to mention walking around half the time with the tops of their heads taken off. So it should come as no surprise that poets can easily lose sight of the workaday world and its oh-so-conventional ways. As a result, even the kindliest poet’s manners can leave something to be desired.

Having undertaken a careful study of the social habits of poets for well over a decade, I’ve compiled a catalogue of some typical behaviors, accompanied by suggestions for improvement. Some of these observations might seem too obvious to mention, but one must never underestimate a poet’s ability to toss etiquette out the window, especially when encountering other, more famous poets. Other examples may seem so absurd or extreme that they could only have been invented for comic effect. On the contrary, all incidents cited have been taken from real-life conversations, situations and correspondence; however, identifying details have been changed to protect the decorum-challenged but otherwise lovable poets who daily enrich our lives.

Greetings from the Id

When encountering friends and acquaintances it is customary to greet them. This means acknowledging them, asking about absent loved ones and/or their health, and expressing enthusiasm, or at least faking it. When meeting people for the first time you should convey pleasure at making their acquaintance. In a foreign locale, commenting on the surroundings is also recommended. Remember: “Hello” is a great place to start.

Whether you know someone already or are meeting a person for the first time, at home or abroad, leading with career triumphs is never in good form. As tempting as it may be, don’t let the Id speak for you, at least not in the first five minutes. Though these days the Superego is an underutilized muscle, even poets can learn to flex theirs once in a while, and to great effect. Just make sure to exercise caution when starting any new fitness regime and take care not to pull anything.

How poets say hello:

- “I got a Stegner.”

- “My essay on irony finally came out in the Field magazine [sic]. You should read it. It’s excellent. Can you get me a job at Harvard? Are you going to Breadloaf? No? Well, can you write me a recommendation?”

- “Did you see the piece I published about Szymborska and Brenda Chamberlain in the latest issue of Five Points? It’s 50 pages!”

Appropriate greetings:

- “Hello. Nice to see you.

- “Hello. How’ve you been? How’s your wife (husband/mother/son/Rottweiller)?

- “Nice to meet you. This is an amazing cathedral, isn’t it? Krakow is lovely.”

Awareness of Others

At social gatherings such as meals or cocktail parties or receptions, where conversation between guests naturally occurs, it is polite to show an interest in every participant you encounter, not just your familiars or your idols. Making strangers feel welcome and included is an ancient and venerable custom; just ask Homer.

Unfortunately, when it comes to conversation, the wonderful camaraderie and mutual regard among poets tend to leave non-poets in the lurch. Poets should keep in mind that prose writers are people, too, worthy of the occasional nod or question, despite their lack of lineation, their thicker books and higher sales. And let’s not forget the poor souls at the dinner party unlucky enough to have pursued boring non-literary careers such as diplomat or pediatric cardiologist or saint. Even a passing awareness of others in the room allows a poet’s better angel to shine and is a special act of mercy toward people who are not initiated into the mysteries.

How poets converse:

- An exchange of recent poetry news, including publications, readings, panels, residencies, conferences, lectures, sightings of famous and/or drunken poets, sabbaticals, anthologies, reviews, radio interviews, appearances in the New York Times Style section, and ground-breaking collaborations with jazz musicians, visual artists, filmmakers, and composers of lyric opera.

- Reminiscences of lesser-known dead poets—surely you’ve heard of Eli Siegel or Yvor Winters or Babette Deutsch or Elder Olson’s The Cock of Heaven—their poems and presses, books and laughable reading styles, which recollections soon devolve into scholarly flame-throwing and friendly but heated one-upmanship.

- A catalogue, easily lasting half an hour or more, of the girlfriends of Larry Levis.

Appropriate conversational gambits:

- “Where are you from?”

- “What sort of work do you do?”

- “You make such a lovely couple. How did you two meet?”

The Personal is Not Poetical

Life’s most difficult, painful moments require difficult, painful communications. When sending condolences, you should take care to express yourself in a suitable manner, with tact and good sense. Aim to convey your sorrow, compassion and affection. If your mentor has died, don’t rush to be the first to post it on Facebook; your mentor’s spouse might want that privilege. When informing a friend, colleague or teacher that you’ve fallen ill and received an alarming diagnosis, simple directness is the best conveyance.

Sadly, the machinery of poetry prizes, prestige, and publishing doesn’t grind to a halt when someone gets sick or dies. Even so, a condolence letter/call/email should convey only condolences. A revelation of ill health should honor the personal connection, not the poetical one. Needless to say, career concerns rather spoil the effect of genuine concern. Professional news and requests belong in a separate message. Wait a few days, or even a whole week, to get back in touch for pressing poetry business.

How poets convey sympathy and sad news:

- “I was devastated to hear that your daughter passed away. I can’t imagine what you must be going through. I thought I made it clear that I don’t use email, so how can I submit my recommendation for the Guggenheim? The deadline is next week. This is very frustrating. You are in our thoughts and prayers.”

- “Please excuse the delay in getting back to you about your fine poems. In the end we did not have room for them. I’m sorry. On a more personal note, I’ve thought of you often, especially since your husband’s death. I am heartbroken for you.”

- “I wanted you to know I’ve been diagnosed with congenital caput tumidus syndrome and am undergoing treatment, which has been difficult. Also, remember that poem I workshopped last summer? It’s coming out in Nimrod. And would be you be willing to write me a recommendation for Warren Wilson?”

Appropriate ways to convey sympathy and sad news:

- “Words cannot express my sorrow for your loss. Sending much love.”

- “I was so sorry to hear about your father’s death. Please let me know if there’s anything I can do for you or your family.”

- “I’ve been diagnosed with severe chronic loquiria. Thank you for all your generous support over the years. It means so much to me, especially now.”

Madness of the Mic

Versifying is a lonely calling. Who could blame a poet for craving a little human contact and attention? Public events—readings, talks, interviews and panels—give poets the chance to teach, to inspire, to connect with, challenge and move people, all with the mighty power of their words. Afterward they get to meet their admirers, who hopefully will buy books and clamor to have them signed. In order to control ego inflation, poets appearing in public should think of themselves as servants of the art and act accordingly.

When taking the podium, bards beware: applause is a highly addictive substance and a microphone the gateway to madness. Get yourself all wired up on public approval, and you’ll only want more. And more. Exercise self-control. Approach each performance with the proper respect for an audience’s patience, because staying home to binge-watch Netflix is always an option. Next time you’re tempted to indulge the all-too-human impulse to yammer on, repeat this simple prayer: Lord, set a guard over my mouth. Then go ahead, enjoy the warm glow of praise, knowing that soon you’ll return to the real world, where no one cares what a sonnet is, much less a sestina.

How poets act at public events:

- 10 poets are reading, with a strict time limit of 5 minutes each. First poet reads for 13 minutes.

- Poet introduces a poem so exhaustively that reading the poem is redundant.

- Poets read their work as if they were _______ [e.g. a prophet, a davening rabbi, a standup comic, an auctioneer, a scholar of their own poetry, at the therapist, bored senseless, Meryl Streep intent upon another Oscar, Bing Crosby crooning in a road movie, rooting for their poems to be better, trying to get back to the hotel in time for the Super Bowl].

- Poet (who has already read) laughs or calls out loudly from the audience in an attempt to overshadow poet at the podium.

- Poet at a tribute memorializes dead poet with the touching tale of how _______ [e.g. dead poet picked my book for a prize; dead poet believed in me when no one at Iowa did; dead poet loved me like a best friend/parent/sibling; dead poet inspired me to write this poem, which I will now read; dead poet condescended to me once and I’ll never forget it].

- Poet interviewing more famous poet asks questions longer than the answers.

Appropriate ways to act at public events:

- Stick to the time limit. When in doubt, read less. People will thank you.

- Keep patter to a minimum. Short jokes are fine. Longer ones, not so much.

- Read your work as if you take it seriously, but don’t take yourself too seriously.

- Let the poet at the podium have the glory, for pete’s sake. It’s over so fast.

- At a tribute evoke the late poet, as a person and a creator. Do not evoke yourself. Nor should you read your own work, no matter how inspired.

- Don’t hog the interview, even if you are more intelligent, articulate and deserving of eminence than the poet you are interviewing.

Wherefore Art Thou FoMEO

Even though “famous poet” is a well-worn contradiction in terms, ample opportunities still exist to make and burnish a poet’s reputation. These include the publication of individual poems in more or less obscure literary journals; the release of a book or chapbook; reviews of said book or chapbook, hopefully favorable, though any attention is better than none; profiles and interviews; a coveted spot at a residency or conference; a cameo in a low-budget documentary about a more famous poet; prizes, fellowships, grants, job offers and lectureships. While poets certainly have a right to enjoy whatever successes come their way, they should try to handle any achievement, be it small or smaller, with humility and gratitude.

Maintaining the proper perspective can help a poet take success in stride. Keep in mind that a poem, however clever or moving, will not feed a starving child or cure cancer or broker peace between warring nations. Likewise, a pat on the back from Bill Murray at the Bridge Walk doesn’t make you a rock star. Poets should avoid the temptation to trumpet their every exploit over the Internet, the phone and the grapevine. Save your latest poetic accomplishments For Mom’s Ears Only (code name: FoMEO). For never was a story of more woe, than this of poets and their FoMEO.

How poets handle success:

- Endless self-promotion via email and social media, announcing publications, readings, reviews, mentions of poetry bestseller lists, honors, appearances, etc.

- Inventive forms of boasting, including:

1. Boasting about sales (yes, really!)—”My editor’s ecstatic, A Place Like Heartbreak sold over 5,000 copies!”

2. Boasting as complaint—”Ugh, I’m so busy on my book tour I had to get a cat sitter!

3. Boasting as inquiry—”How do you put Bellagio on your CV?”

4. Boasting as scheduling trouble—”I can’t make it next week. I’m keynoting at AWP.”

5. Boasting as clarification—”Hey, I got a MacArthur, too.”

- Ingratitude, including:

1. Gripes about neglect—Pulitzer-/National Book Award-Winning Poet: “I don’t get enough readings. Young people don’t read my work. And my last book only got five reviews.” Prolific Celebrated Poet: “It’s an outrage, I didn’t win a prize this year.”

2. Compliments taken as insults—Poet 1: “I love your book The Beast Inside the Beast.” Poet 2: “What, you don’t like my other work?” Poet A: “Your poem ‘Hiatus’ is one of the great villanelles of the 20th” Poet B: “There are two great villanelles in that book.”

Appropriate ways to handle success:

- Save group emails and postings for major events only. Once a year, maybe twice, is sufficient to notify us about your poetic doings. Updates are not necessary.

- Don’t boast. Not only is bragging unappealing, there’s always another poet with a better boast than yours. Also, FYI: “keynote” is not a verb.

- Be grateful for what you have, rather than bemoaning what you lack. Look, you’re lucky Knopf still has a poetry list. Things could always be worse.

Plug the Leaks

Despite, or perhaps because of, the relatively minor material perks, writing poems is indeed a noble calling. Throughout the ages and across the globe poetry has provided consolation for readers amorous and abandoned, joyful and vengeful, celebrating and grieving. However, a devotion to the art need not entail a desertion of decorum. No matter the situation, poets should always try to hold themselves together, keep their worst impulses in check and behave well. Emily Dickinson likely had this in mind when in “Those who plunder sunken gold” (#2311) she famously warns: “Those who plunder sunken gold – / The ocean’s sacred gift – / Can never bear their treasure home / Upon a leaky craft.” So before you set your sights on faraway shores, heave up your anchors and sail away, dear poets, be sure to batten down your hatches and plug up your leaks!