Meeting the Sealey Challenge

by Liz Garcia · September 24, 2025If you’re a writer, you have at some point received the advice to read, read, read. William Faulkner’s statement, in a 1956 Paris Review interview, to “read everything –trash, classics, good and bad, and see how they do it,” is often quoted to exemplify this advice. Though I can’t say that reading “trash,” has ever benefitted me, I can say that as a poet, one of the best ways I have immersed myself in good poetry—to recuperate my brain from the “trash” of everyday noise—was to take on the Sealey challenge: to read one poetry book per day during the month of August. When I recently decided to take on this challenge, I knew it would help me kickstart my brain after the summer break, and help me familiarize myself with some of the ecopoets I’d recently decided were germane to my next project. What I didn’t realize was how much the exercise would help me uncover insights in my own writing process.

The Sealey Challenge is so named for its founder, poet Nicole Sealey, who decided in 2017 that she wasn’t making enough time to read poetry for pleasure, and created a challenge among her colleagues. (You can read more about its history here, as well as link to ASU’s collection of free resources for this challenge, especially helpful for those who can’t purchase books). Over the last eight years, it has spread wide enough through social media circles to have its own #sealeychallenge with upwards of 5,000 posts on Facebook alone.

What made me decide to take it on this year was a bit of serendipity; in a Facebook group, Erin Murphy, author of Human Resources and other titles, proposed that those with recent books share and read each others’ work. I jumped at the chance to have someone else read and promote my own book Resurrected Body, which was published in 2024. In the process, it dawned on me that August would be the perfect opportunity to actually participate—that reading a poetry book per day would help awaken my right brain in preparation for the semester of writing classes. And after a slow summer with my three kids, in which most of my writing consisted of trying to take notes on my phone, I knew I needed something to help myself remember how to think like a poet. On August 1, my daytime hours would be mine again to think about writing, and turn my attention to what I’d recently decided would be my MFA thesis project—an ecopoetry collection.

But I’d also recently tried to develop a Substack presence (which I now feel requires a degree program of its own), and saw an opportunity to build up my content: I’d write something about each book I read. Knowing that this could easily derail the already lofty goal, I decided: this is for myself and no one else. I’d take a reader response, more personal approach, not pressuring myself to write a “review” as I might for a journal. I’d immerse myself in beautiful language without the pressure of writing poems, and I wouldn’t worry about finishing every word of the book–just enough to feel my synapses remember the pathways of metaphor, and to come up with some salient observation.

Despite my low stakes decision to not worry about writing poems, what I discovered is that I kept being surprised by my own ideas wiggling their way through. I’d take a book on my morning walk through my neighborhood, which, unlike others in the suburbs, is filled with old pines and hardwoods, frequent wildlife. And I’d find myself pausing to notice their particularities, to become present and mindful, to take notes, jot down lines that came to me, seeds for my own poems. Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s Oceanic, for example, awoke my brain to ways to address the millipede, the nest of webworm moth, the elusive tanager. Andrea Jurgevic’s most recent book In Another Country, with its incredible rhetorical turns, helped enliven my vision and comprehend new ways to navigate the dimly lit pathways of my own unborn poems.

Reading Craig Santos Perez, Joan Naviyuk Kane, Camille Dungy and Eleni Sikelianos, I became familiar with the varieties of ecopoetics, the possibilities of form and rhetorical stances, and began to see ways that I could participate in the conversation as an acolyte, even one in the suburbs who is admittedly not yet fully living the green gospel of conservation. (When my kids were babies, for example, I had friends who used cloth diapers. That, I felt, was asking too much in an already daunting endeavor.)

But I also discovered opportunities to make personal connections. I read books by people I knew, which was mutually beneficial: writing about them was a way to promote their work, a way for them to feel seen, as well as a guaranteed audience. Reading some collections, like Maurice Manning’s Bucolics in my early morning hours, fired my synapses in the direction of spirituality, something that was easy to share on social media. And Andrea Gibson’s work literally moved me to tears, articulating a cosmic compassion that I could share with many friends who don’t consider themselves poetry readers. Though I can’t say with certainty how many other people were changed by my writing about poetry, I know I was.

***

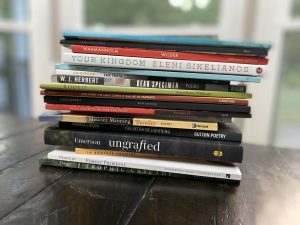

So did I meet the “challenge” of 30 books? Not exactly. I won’t lie, the weekends got me. Kids were around, things got busy. But who was I going to let down? I made the rules. So I’d push weekend entries to Monday, combine them, or just skip a day (who cares!). One of those days turned into a lament at not having the time to read at all—which became a poem (of sorts) of its own. And when my semester started back, my Substack writing understandably petered out. I ultimately read 21 books, and wrote about 20 of them. If there’s a failure here, it’s that I didn’t put one of Nicole Sealey’s books on the list. But then—so many poets, so little time.

I won’t say it was a failed experiment. What it did for my brain alone was invaluable. I swear there were a few days when I felt I could SEE the world in terms of poetry, I could SEE the poems I needed to write, I just needed to jot down notes to myself, and make time to write them. Looking back at my notes some days, there’s a fog shrouding that vision, and I can’t remember what it looked like.

But I have faith in that process. I’ll read more poetry, and it will open me again. The words will come, even if at times, that part of me falls back to sleep.

Elizabeth Garcia is the author of Resurrected Body (Cider Press Review, 2024) and Stunt Double (Finishing Line Press, 2016). She received a BA in Humanities from BYU, an MA in English Lit from VSU, and is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at GSU. She’s a Georgia native, mother of three, and amateur family history buff.