Madame Bovary: What is food if you can’t consume it?

by Karen Sims · September 26, 2022

Madame Bovary is a food novel: food echoes itself across the narrative, and Flaubert uses food to highlight the characters bourgeois angst. However, Flaubert’s use of food is almost antithetical to the way food is used in contemporary literature and writing. Modern food writing is all about recreating the meal, the experience of eating. On the other hand, while there is so much food in Madame Bovary–nobody seems to eat! Well, except for Charles. Poor, hungry Charles. The only time we, as readers, see Emma eat, to truly exist in the moment of consumption, is when purges, or when she commits suicide by ingesting poison.

Take the wedding banquet, for example, where despite the intricate visual and technical details, there was no mention of what the food actually tastes like. In fact, some of the dishes sound downright impossible to reproduce. They are more the idea of food than a realistic portrayal of food. I’ve always thought of food writing as a practice in synesthesia, of trying to place taste on the page as something consumable, accessible though reading, instead of chewing. Flaubert’s treatment of food is noticeably anti-eating, and on the surface, this makes his food writing almost anti-food itself, which I think, is an important point.

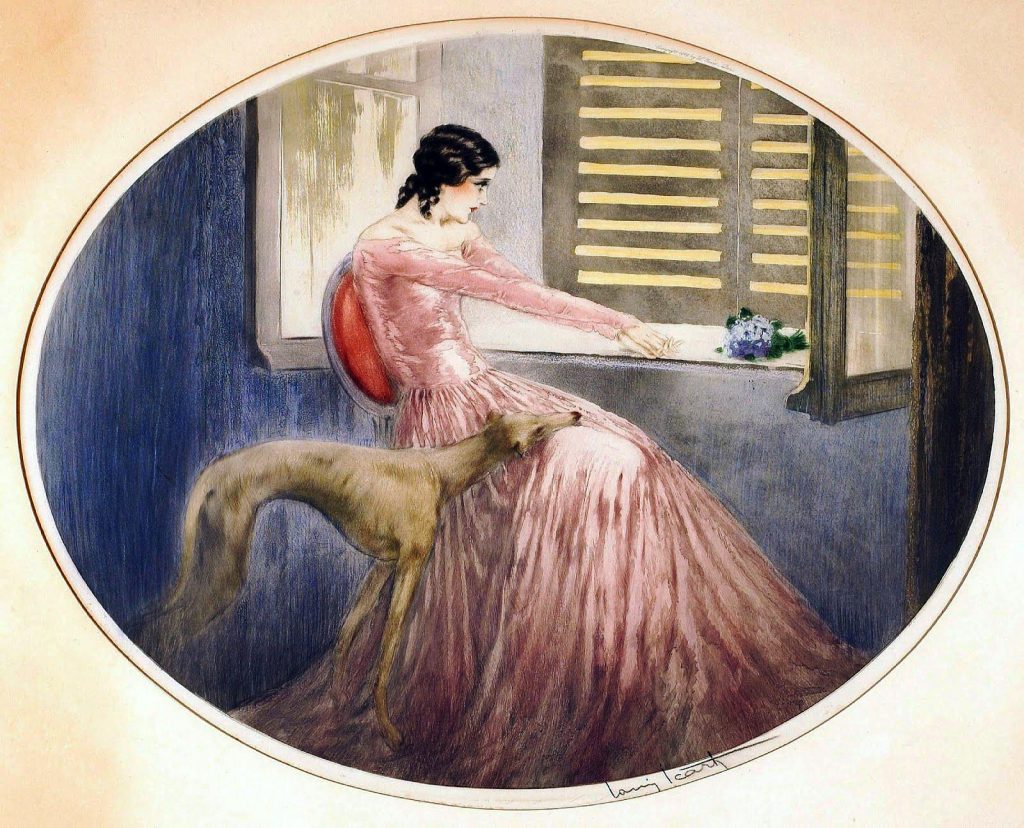

Instead, food, like fabrics and gaudy decorations, are used as markers of class in Madame Bovary. In fact, one moment we do see Emma eat actual food is at the fancy banquet at the chateau. She eats a “maraschino ice,” a delicate ice cream or sherbet. This is a moment when she is acutely aware that while she is no longer a peasant, yet she is also not part of the upper class. The bite of ice is an illusion she shrouds around herself. Again, there is no description of taste–only of the spoon she bites into, which would have left a metallic, sour, and artificial sensation on her tongue.

There are many, many food moments that echo this one. Emma often sets or notices fancy dinner tables, but her fascination is with the place setting, the appearance of food, over the actual meal. While she diets and drinks vinegar to lose weight, she is enamored by fancy foods like pineapple and pomegranates. Yet she doesn’t care about the remarkable tropical aromas or bursting sensation of the berry–she cares that rich people’s sugar “seemed to her whiter and finer than elsewhere.” Later, middle class Yonville is described as having bad cheese, and lower class restaurants are described as smelling of “absinthe, cigars, and oysters.” She doesn’t really taste any of this. She definitely doesn’t eat it. It’s just a medium for her to understand her own wealth, or lack of it.

Perhaps food is only used symbolically in Madame Bovary, and it is used primarily to denote class, Emma’s psychology, and her dissent into ruin. It’s used to show societal separation and hierarchy. To show Emma enjoying herself in food might equalize her to both the peasants and the upper class, something Emma’s status-obsessed psyche would never allow. On the other hand, Charles eats all the time. In fact, he becomes fat over the course of the novel. He, unlike Emma and the other middle class people, is less concerned with upward mobility or appearances. He is actually capable of tasting his beef hash, although he is oblivious to everything else.

As a food writer, I’ve written politically charged pieces and decadent, voyeuristic reviews. But I’ve also written click bait, where the photo means more than the words (in fact, I was paid by the word count). I did this to pay the bills, to try and climb into a certain financial bracket, the very bracket I was writing for, nine to fivers looking for a quick read during their lunch breaks. I openly chose content over craft, production over process. I stopped writing about food as if I actually enjoyed it, but as a sign of social acceptance, of having a “real” job that brought in “real” money and status. It became my Maraschino ice. I, like Emma, had stopped tasting.

Then I went back to school, where I had to read Madame Bovary for a Form and Theory course. Thinking about Flaubert’s use of food as craft has now reinforced my opinions about labor, class, and eating. We can’t all eat the same things, that’s a fact. Some will have gold-flaked caviar on truffles. Some will have salmon roe and shiitakes. And others will make do with a scrambled egg dinner. Which foods are classy and expensive are subject to the whims and preferences of those few who have the most. Even lobster was once served in prisons. But there’s one thing the upper class can’t steal from the lower classes, then sell to the middle classes–along with an unachievable dream of class climbing. They can’t steal taste. They can’t steal that moment of enjoyment, when even the cheapest meals, the most desperate meals, hit a person’s tongue. That seems to be something Charles, despite his ignorance, could understand. Unfortunately, it was something Emma forgot: eating is not just a show of status, it can also be a rebellion against it.

Supplemental reading: The Paris Review’s “Madame Bovary’s Wedding Cake” by Joachim Kalka

Karen Sims is a PhD candidate and Graduate Teaching Assistant at Georgia State University. Her fiction, creative nonfiction, and food writing have appeared in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, MSU Roadrunner Review, Put A Egg On It, and others. Her story “Raohe Night Market” won the 2024 Steven R. Guthrie Memorial Writers’ Festival Contest in fiction. Originally from Taiwan, she also publishes under the name 蘇祺 Suqi Karen Sims. Her research interests include nonwestern narratives, myths, and food as literary device. She is an Assistant Editor at Five Points.

Karen Sims is a PhD candidate and Graduate Teaching Assistant at Georgia State University. Her fiction, creative nonfiction, and food writing have appeared in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, MSU Roadrunner Review, Put A Egg On It, and others. Her story “Raohe Night Market” won the 2024 Steven R. Guthrie Memorial Writers’ Festival Contest in fiction. Originally from Taiwan, she also publishes under the name 蘇祺 Suqi Karen Sims. Her research interests include nonwestern narratives, myths, and food as literary device. She is an Assistant Editor at Five Points.