Graphic Novel Reframes Literature: Jesse L. Kercheval Interview

by Alicia Raines · October 20, 2025Graphic Novel French Girl Reframes Literature: Jesse L. Kercheval Interview

Behind the Scenes of A Graphic Novel That Combines Art, Poetry, and Non-Fiction

By Alicia Raines

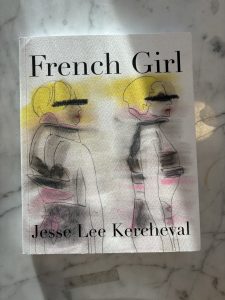

Jesse Lee Kercheval is a novelist, poet, short story writer, translator, and graphic novelist. Her graphic essay, “Birds,” was published in our most recent issue of Five Points (Vol. 24. No. 1), and her first graphic novel, French Girl, was published in 2024 by Field Mouse Press. Assistant Editor, Alicia Raines, interviewed Kercheval about the role of illustration in story-telling, and how graphic novels can have a deeper impact for the artist and the reader.

Read their conversation below.

You write novels, short stories, poetry, memoir, and comics. When you set out to tell a story, how do you know what container it is meant to fit in? For example, how did you know “Birds,” a graphic essay published by Five Points, was a graphic essay, not a poem?

Which form or genre I choose for an idea is a question that first came up when I began writing poetry in addition to fiction. Then the question was, How do you know if an idea should be a poem or short story? It’s a great question but, to be honest, I am always a b it unsure about how to answer it. All I can ever say is that each idea comes in its given form. For some reason, I never walk around with an idea thinking, Novel or poem? Short story or graphic essay? The idea just arrives as a story, arrives as a poem. Generally speaking, fiction starts with characters and a situation that puts pressure on those characters. I write to see where the story takes them. I often walk around thinking about prose for a long time before I start writing, working it out in my head. Poetry starts with language, with voice—a word or line that just takes hold of me. I never know where a poem is going when I start. The easiest part of this question to answer is why “Birds” a graphic essay (and not a poem, novel, or all word essay). “Birds” grew from my daily drawing. My comics/ graphic essays/ memoirs almost always start with the art. I draw, just draw, usually a group of images, then a story starts to form around that. So art first, not words.

it unsure about how to answer it. All I can ever say is that each idea comes in its given form. For some reason, I never walk around with an idea thinking, Novel or poem? Short story or graphic essay? The idea just arrives as a story, arrives as a poem. Generally speaking, fiction starts with characters and a situation that puts pressure on those characters. I write to see where the story takes them. I often walk around thinking about prose for a long time before I start writing, working it out in my head. Poetry starts with language, with voice—a word or line that just takes hold of me. I never know where a poem is going when I start. The easiest part of this question to answer is why “Birds” a graphic essay (and not a poem, novel, or all word essay). “Birds” grew from my daily drawing. My comics/ graphic essays/ memoirs almost always start with the art. I draw, just draw, usually a group of images, then a story starts to form around that. So art first, not words.

You only began working in comics a few years ago, during the pandemic. How has venturing into graphic works elevated or transformed your stories? What can it accomplish that non-visual stories can’t?

I think graphic work enabled me to reach deeper into my memories and emotions. When I put pencil or pen to paper and draw, something unexpected happens every time. When the drawings began to connect and form a story, they reach a different place, even when it is material I have dealt with before. I published an “all words” memoir Space in 1998. Some of the material in French Girl overlaps with it—growing up in Florida during the moon race, breaking my back falling from a tree. But I didn’t use that material—ie illustrate Space, using language from Space, for parts of French Girl. I just drew and as I did, I went back in time to those moments, to memories that had not been processed into words, turned into oral or written stories. What I found was more emotional, more dreamlike.

I know that you are friends with the Queen of Comics, Lynda Barry (I am a big fan!). Are there any other comic artists who inspire you? Any artists (comics or non) whose work you returned to in the making of French Girl?

Lynda is my long time colleague at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. We shared generations of students. I was always hearing from grad and undergrad students about her classes. I often had one of her students come over to do a quick exercise with my creative writing students. A couple of years ago, she very generously let me take her semester comics class. It was life changing. A true gift. She is an amazing artist and teacher. Besides Lynda, the teacher who had a strong influence on my work is the artist and graphic memoirist Sarah Lightman. I took several of her classes online through the Royal Drawing School in London. Sarah made me see much of the art I had always loved as narrative and taught me to think beyond traditional comic panel format. I also love the work of Leela Corman, especially her latest book Victory Parade. She brilliant with color and her ability to turn history into very intimate narratives. And I love with the work of Charlotte Solomon and autobiographical series of paintings Leben? oder Theater?: Ein Singspeil (Life? or Theater?: A Song-play). The paintings tell the story of her life and her family up until her death in the Holocaust. Amazing work.

Can you talk a little about the process of making French Girl? How did you illustrate the pages, did you thumbnail your sketches or dive right in, what materials did you work with?

I did not do thumbnails or sketches for French Girl. Or even plan the pieces in advance, though I have done that for more traditional panel comics. I just drew. I start with a sketch in pencil or pen and then use soft pastels, working them into the paper, which is usually 9 x 12 or 14 x 20. As I mentioned above, I usually I try to draw every day that I am not traveling. Then some of the time, the drawings start forming a story. If so, I write down a simple outline of what I think I need to draw to finish the piece and go back to drawing. I don’t add text until I have finished drawing. Then I write out a script, working to cut the words to an absolute minimum, and add the text to the images. That is the only part of the process that is digital. I’ve done hand lettering in ink before on comics, for example in Lynda Barry’s class, but you can’t really write on soft pastels—it is like trying to ink on dust. So I developed a process of scanning each drawing, then adding the text using Procreate on an ipad. That also lets me correct or change text if needed during the book production process (ie catch typos, add a word or two if something is confusing) without having to redraw the entire image.

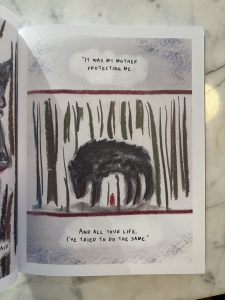

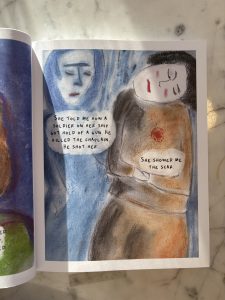

Sometimes there is an outside prompt for a piece. I did some of the work in French Girl during classes I was taking online from the Royal Drawing School. Not graphic narrative classes, just their drawing classes which tend to have rather open themes like Color and Memory or Drawing Internal Landscapes. For each week’s class we would be shown a wide variety of art works, sometimes a book, poem, or movie as well. Then we would draw. Most people in the classes would be working on a single drawing or a series of sketches. I was usually the only one working on making graphic narratives. For example, the piece “Wolf” in French Girl came from a class where we were asked to make a shadow box of our version of “Little Red Riding Hood,” to draw the shadow box. My version folded a story I remember my mother telling me about her grandmother into the usual tale of wolf wickedness. “Winter,” also in French Girl, came from an assignment to draw landscapes with snow and ice. But inspirations comes from other places as well. The last piece I drew for French Girl, after it had already been accepted and I was at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts madly working 16 or more hours a day to get it ready for publication, was “Bang.” In it, art I had just seen in Italy, angels and madonnas breast feeding a strange looking baby Jesus, became the story of depression in women in my family, reaching back through time to the Big Bang.

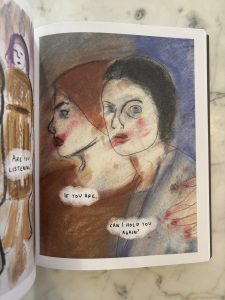

There are so many visual elements in French Girl that add layers to the story. For example, the stories in which you draw yourself with red hair symbolize your bravery (or desire for bravery?), since we’re told earlier in the book that your mother believed red-haired women weren’t afraid of anything. Another strong visual decision is the tool of abstraction versus clarity, such as the “Sister” chapter. When you are asking your sister if she’s there, the details are minimal, difficult to capture. But when you ask if you can hold her, it looks like you’ve physically caught her, like you’ve managed to stop this quick, elusive creature. These illustrative decisions add so much complexity and emotion to the story. How conscious were these decisions? Were they planned ahead of time or did they surprise you, in the same way that writing can be surprising?

During the pandemic, I started drawing women with red hair. Realistic, abstract, comic. I had no idea why really. I have a year’s worth of them, at least, from before I started to work on the type of graphic narratives that form French Girl. One day I realized this was probably connected to what my mother had said about women with red hair being brave. And so I wrote “The Body is a Vessel” which was originally more of an illustrated essay, ie lots of words with some drawings. That version appeared as an essay in Fourth Genre. After that the idea of the red hair became more of a conscious symbol for me. In “Sister,” the very abstract, sort of melted, surreal drawing style was a conscious decision. It gives the piece a fairytale quality—but also reflects how these memories are distorted by time and the pressure of emotion. But when the story comes to the present, to the end, I wanted the images to be sharper. Focused. I will say, though, as usual some of the drawings came first, before the story, so probably it was a combination of an emotional decision (the drawings are blurred because the memories are, too) followed by an conscious one (ah, this style is integral to telling this particular story!). So always a mix of intuition and intellect works best for me. And I have to trust my intuition to lead the way first.

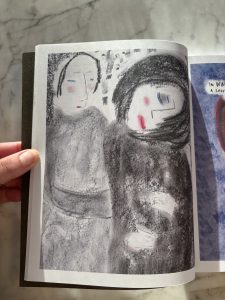

There are a few images that repeat throughout French Girl and in “Birds.” Specifically, these two women looking mournful appear twice in French Girl. And two children leaning to kiss each other appear in both French Girl and “Birds.” Can you tell us what the personal significance of these images are, since you keep returning to them?

The children leaning in to kiss are from one of the few photos I have of my sister and me in Fontainebleau, France when we were little. I find myself using it over and over again, drawing it, collaging it. And the two women, which is not based on a photo or my sister and me, sort of took on the weight of being the adult version of that. I often draw something in different colors to try out the emotions that provokes, or different styles (sharper, more muted, partially erased). But there is a limit to the effective use of repetition. When I was editing French Girl, I took out some repeated images, drawing new ones to replace them. But now, working on new pieces like “Birds,” I find myself using a bit of repetition again. I think to connect the earlier work to the older work.

I have personally discovered that when I’m stuck on an idea, sometimes changing the format helps to loosen the creative block. Have comics been able to unlock otherwise unreachable stories for you? What has the role of comics been in your personal craft as a writer?

I switch genres all the time when I am stuck—maybe not on a particular idea, but just in a dry place with a particular project or genre. I think comics have been great for me because there is, honestly, less pressure on them. This is not because I don’t care deeply about the form or am not (obsessively) interested in making them. But I never went through an MFA in comics (as I did in fiction) or worked on a book of comics for tenure or promotion at a university (as I did with fiction, poetry and memoir). I have never written a grant proposal for a comic. I just started doing them for pleasure—or at least as a distraction when we were in the middle of a world-wide plague I thought might well be the death of me. So I was able to turn off all those inner critics that I let fill my head in a lifetime as a writer. I had no particular expectations when I started and even now, after publishing most of the individual pieces I’ve done and French Girl, I feel the same way. The only thing that matters is that the comics interest me, keep changing and growing as I work on each piece. I think that is also a lesson Lynda Barry taught me and one of the many reasons she is such a great teacher. It is also one I know I tried to teach my students in all my years of teaching, though clearly not one I quite learned myself. I hope that lesson—do the work because you love doing it, that the the work is the reward—has spilled over now into my other work, too.

I’ve read several of your interviews in preparing for this one, and I read that you have never been happier about a book than you’ve been of French Girl. Why is that? What is special about this story and this format?

As I mentioned before, I came into comics with no expectations. I drew. I found a few comics classes online (online classes were the great gift of the pandemic). I read graphic books. There were so many great ones I had never read and new ones coming out all the time. It was discovering a whole new world. Then I started sending individual pieces to literary magazines—like Five Points—because that is my world, where I was used to publishing my work. And they got accepted and published which seemed amazing. And then when I thought I probably had a book, I showed it to Rob Clough at Fieldmouse Press and they gave me a contract for French Girl. The editors, Rob and Alexander Hoffman, were so great to work with, so encouraging. And they cared so very much about the quality of the production. It is a gorgeous book. And when it came out, I got to go to alternative comics events like SPX (Small Press Expo) in D.C which were also completely new to me. This book was like winning the lottery when you didn’t even buy a ticket, just a complete surprise and a joy. Also, I am very proud of it. I do not like, as a mother of many books, to pick favorites. But I do love this one very much.

Are you drawing any new stories now? Can you tell us what it is?

“Birds” is actually an excerpt from another graphic memoir, Household Gods, that will also be published by Fieldmouse Press, probably early next year. I am working on it now. “Birds” is another piece that came out of a class I took with the Royal Drawing School, after a long break. The class was called “Metamorphosis” but for some reason, it still came as a complete surprise to me it was mostly about Greek myths. I have never really been a Greek myth gal. So my response was arguing with them, mixing them into my own life. Thus Household Gods, which is more an adult life memoir. Several others that will probably be in the book have already been published or are forthcoming in Orion, the Black Warrior Review, the Seneca Review, Pleiades and the Rumpus.