Secret Goings-On: Learning from Ray Bradbury and Ernest Hemingway

by Megan Sexton · August 22, 2012 We are proud to present a new guest post by Five Points contributor Hugh Sheehy, whose short story appears in 14.3, our most recent issue (see bottom of the post for a brief bio). Read on to learn more about his take on some of Ray Bradbury and Ernest Hemingway’s works–including connections between the two.

We are proud to present a new guest post by Five Points contributor Hugh Sheehy, whose short story appears in 14.3, our most recent issue (see bottom of the post for a brief bio). Read on to learn more about his take on some of Ray Bradbury and Ernest Hemingway’s works–including connections between the two.

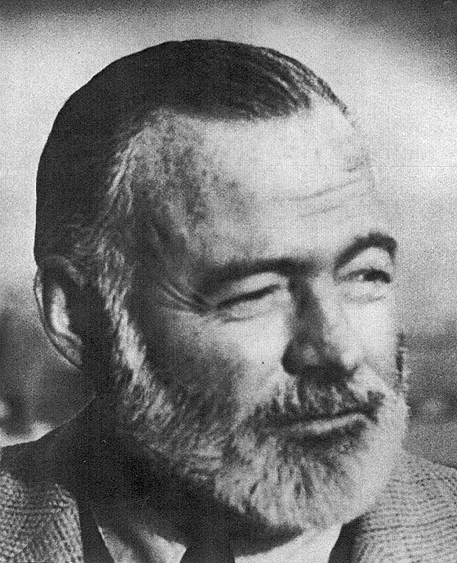

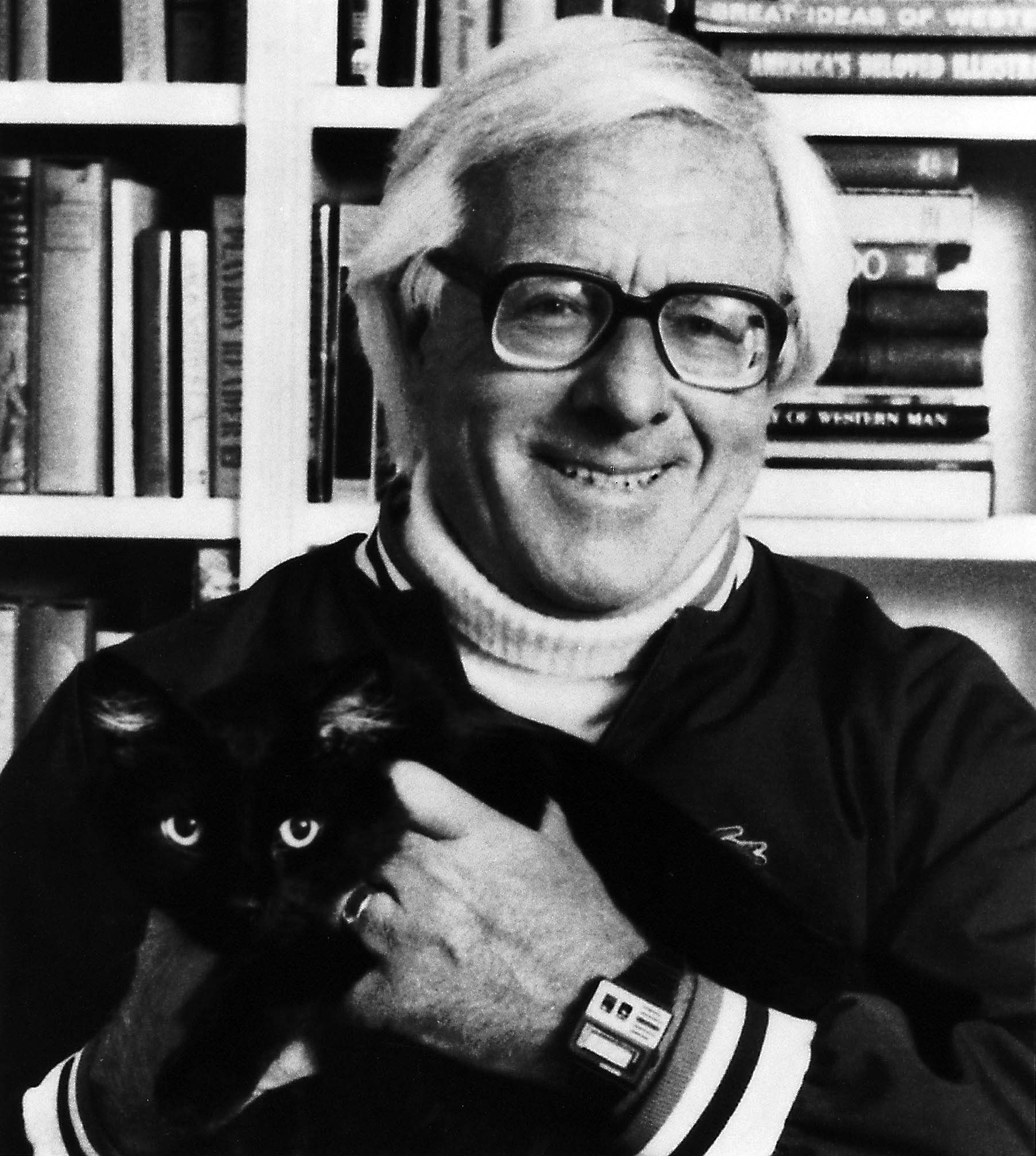

By my count, Ray Bradbury wrote for five new generations, including his own, in his lifetime. This is to say nothing of those readers, radio listeners, and (eventually) television and film buffs who were mature or getting there when he was born in 1920. Some of his early readers had surely been alive to see the Civil War, and one can only speculate about how wonderful, strange, and perhaps painful visions such as his must have been for them. Given the widespread displays of remembrance and grief when he passed away last month, it seems assured that many future readers will pick up his books. My daughter, who was born May 6th of this year, has already listened to me read a number of stories from The Illustrated Man. While it would be a stretch to call her a devotee, I can say that she appears captivated by the consonance and rhythms

Rereading The Illustrated Man, I have been struck by the spare force of Bradbury’s sentences. I have also noticed that it is difficult to overlook the apparent influence of Ernest Hemingway, whom Bradbury not only read avidly but also spoke and wrote about in many places and publications. This is not to devalue Bradbury’s writing in any way. Rather, what I’d like to do is describe in brief what I see as his contribution to the craft of short fiction. In reading Hemingway, Bradbury must have observed that Hemingway was not just telling stories. He must have observed that Hemingway was telling stories in ways that allowed his audience to see storytelling in new ways: that they were a kind of art. I believe that Bradbury’s discovery of this side of Hemingway can be witnessed through Bradbury’s contributions to the fields of science fiction and horror, to which he is generally viewed as having introduced a literary dimension.

Bradbury’s style in his short fiction points most directly to the Hemingway stories published in In Our Time. Take the well-known opening of “Indian Camp”:

At the lake shore there was another rowboat drawn up. The two Indians stood waiting.

Nick and his father got in the stern of the boat and the Indians shoved it off and one of them got in to row. Uncle George sat in the stern of the camp rowboat. The young Indian shoved the camp boat off and got in to row Uncle George.

The two boats started off in the dark. Nick heard the oarlocks of the other boat quite a way ahead of them in the mist. The Indians rowed with quick choppy strokes. Nick lay back with his father’s arm around him. It was cold on the water. The Indian who was rowing them was working very hard, but the other boat moved further ahead in the mist all the time.

“Where are we going, Dad?” Nick asked.

“Over to the Indian camp. There is an Indian lady very sick.”

“Oh,” said Nick.

Across the bay they found the other boat beached. Uncle George was smoking a cigar in the dark. The young Indian pulled the boat way up on the beach. Uncle George gave both the Indians cigars.

They walked up from the beach through a meadow that was soaking wet with dew, following the young Indian who carried a lantern. Then they went into the woods and followed a trail that led to the logging road that ran back into the hills. It was much lighter on the logging road as the timber was cut away on both sides. The young Indian stopped and blew out his lantern and they all walked on along the road. (Hemingway 15)

This is an extraordinarily accomplished passage. Let me count some of the ways, beginning with the most well-known. The language is concrete with few modifiers. It presents the reader with a sequence of logically interconnect-able images that create questions about what images, some of which can be construed as events, will follow. In other words, the sentences tell story directly and concisely. Dialogue creates a larger context. Characters and their relative familial and social are accomplished thought both naming and not-naming (while Hemingway’s attitude toward these Ojibwes may not seem charitable or fair, it is essential to representing the white, male, patriarchal point of view that the short story ultimately works to undermine). The story has also introduced and begun to exploit two thematic elements that work together throughout the piece to demonstrate Nick’s ironic coming-of-age at the Indian camp: mystery and apprenticeship. The former is conveyed through the figures of the canoe on the shore of the misty lake and the speechless Indian figures, who exist here as moving bodies and guides to the unknown camp, strange Chirons who will ferry them to a place where Nick will learn something of death. As for apprenticeship, the dialogue makes clear that Nick’s father is taking his son with him to work with him, in this case as a doctor making a serious house call. A few paragraphs after those supplied here, his father will refer to him as an “interne” while providing the boy with descriptions of the Caesarean section he is performing on a pregnant woman. Nick’s father is grooming his son, however fancifully, to become his replacement. The story also has begun with a group of males taking a boy with them as they go to help a woman, which prepares the palette for the contrasting images Hemingway will provide of men and women coping with pain in sharply different ways. He has also placed the figure of the white male doctor–one of the most prestigious in Western society–in the classic position of the hero, though the reader’s access to him is limited by the Nick’s perspective. The central placement of Nick’s father is accented heavily by his uncle’s distribution of cigars before the doctor has even begun the operation–as if it is a foregone conclusion that it will be successful!–and together these elements create a suspenseful question for the reader as to whether he will succeed in his errand in the Ojibwe camp. The embarrassed answer the story provides–the same verdict on manhood delivered throughout In Our Time–is fundamental to a transformation of the American hero that resonates throughout much of the literature written since.

And here is the opening of Bradbury’s classic story “Kaleidoscope”:

The first concussion cut the rocket up the side with a giant can opener. The men were thrown into space like a dozen wriggling silverfish. They were scattered into a dark sea; and the ship, in a million pieces, went on, a meteor swarm seeking a lost sun.

“Barkley, Barkley, where are you?”

The sound of voices calling like lost children on a cold night.

“Woode, Woode!”

“Captain!”

“Hollis, Hollis, this is Stone.”

“Stone, this is Hollis. Where are you?”

“I don’t know. How can I? Which way is up? I’m falling. Good God, I’m falling.”

They fell. They fell as pebbles fall down wells. They were scattered as jackstones are scattered from a gigantic throw. And now instead of men there were only voices-all kinds of voices, disembodied and impassioned, in varying degrees of terror and resignation.

“We’re going away from each other.” (Bradbury 26-27)

This was true. Hollis, swinging head over heels, knew this was true. He knew it with a vague acceptance. They were parting to go their separate ways, and nothing could bring them back. They were wearing their sealed-tight space suits with the glass tubes over their pale faces, but they hadn’t had time to lock on their force units. With them they could be small lifeboats in space, saving themselves, saving others, collecting together, finding each other until they were an island of men with some plan. But without the force units snapped to their shoulders they were meteors, senseless, each going to a separate and irrevocable fate.

A period of perhaps ten minutes elapsed while the first terror died and a metallic calm took its place. Space began to weave its strange voices in and out, on a great dark loom, crossing, recrossing, making a final pattern.

“Stone to Hollis. How long can we talk by phone?”

“It depends on how fast you’re going your way and I’m going mine.”

The places where the styles match are easily enough noticed. Bradbury uses the same direct and concise writing to create a scene and give it a context. He uses names and dialogue to enrich that context and give the story direction and suspense. Names differentiate characters in the manner necessary to this story, where it is what the men (there’s really no good reason, aside from the time this was written, for the story to lack female astronauts) share in common that is important to the tale’s overall meditation on how time makes one’s antagonists into figures remembered fondly, maybe even into figures essential to one’s sense of identity. The last two lines of dialogue set up the radio drama that will play out through the rest of the story, as the astronauts hurtle through space to their respective deaths, all the while talking to friends, cursing enemies, and, in the case of the central character Hollis, coming to terms with the kinds of people they have been until now.

There are important differences, too. First of all, Bradbury’s writing is more poetic. He uses analogy freely, whereas Hemingway’s prose is concentrated on presenting a world as-is (as opposed to a world as-like). This arises not only from the pressure Bradbury might feel as a writer dealing with materials readers have most likely not encountered firsthand; it also arises from a passion for visionary imagination that is notably absent in the Hemingway piece. Take, for example, the sentence “The men were thrown into space like a dozen wriggling silverfish”. Bradbury might simply have written “The men were thrown into space,” a statement that provides the visual element necessary for the story to proceed. However, he attaches the analogy “like a dozen wriggling silverfish” to endow the story with a new quality, a kind of dazzling effect that is accomplished by a few specific details. The use of the continuing tense in “wriggling” creates motion and also gives the modifier a feeling of endlessness; the compound “silverfish” also does double duty, in that the reader sees the words “silver” and “fish” (which together produce a flashy image) while also recognizing that Bradbury is comparing the astronauts to a benignly verminous insect (and hence insignificant, pesky at most, in the broad scheme of the universe). Finally, the effect is limited by “dozen,” which gives the reader (this reader, anyway) a number that can be visualized only briefly because of the mental effort required in imagining twelve more-or-less-identical-yet-distinct astronauts flying willy-nilly from a rent vehicle in outer space. When added through simile to the simple statement “The men were thrown into space,” those three words “dozen wriggling silverfish” set off a small and pleasant fireworks display in the reader’s mind; they also give way to a feeling of distress, because the wriggling figures are visibly alive. It is this secondary level of imagination, describing a world as-like, where the narrative’s principal figures undergo transformation temporarily, that sets Bradbury’s style apart from Hemingway’s (which is not to suggest that the style is without its own problems, but only that Bradbury found this way to move past his predecessor).

The other major difference lies in the selection of narrative content. While this may seem obvious, I would argue that Bradbury’s interest in science fiction and horror arises from the same faith in imagination revealed by his stylistic leaps into a secondary realm of figuration. Bradbury trusted the imagination to take him somewhere, to lead him through a kind of story-making that would not only recount a sequence of events but also signify something to his reader. In the case of “Kaleidoscope,” a story widely anthologized and adapted to other media, Bradbury’s trust in his vision wound up leaving us with a sad, profound, and strange tale about doomed astronauts which cannot help but remind us of how our own paths in life have taken us away from both enemies and friends and how those figures, growing ever distant, are both dear to us and part of who we are. That is to say, his story reminds us that the people we know and have known belong to the stories we each tell ourselves about who we are.

I am not interested in ranking these two authors against each other. Each has made his own mark, and each will be around for at least some of the unforeseeable future. However, it may be useful to note the difference in their attitudes towards their work and their lives. They were writers of different temperaments, as Bradbury suggests here, in a letter he wrote his friend and early publisher August Derleth in 1944 or 1945:

“Hemingway strikes me as a man who has a steel grip on his mind and is afraid to let go, for fear of finding out that he is some species of lovable, sentimental, ordinary jelly-fish underneath. He seems a little too preoccupied with being hard, and that fairly well indicates a lot of secret goings-on in his mental life.” (Eller 81)

“Secret goings-on” is a way of talking about dreams and hopes (to the extent they can be separated) that one conceals for fear of embarrassment or shame or some kind of social punishment. It is easy to hide our dreams when prevailing cultural narratives present pictures of economic, political, and social decline, when so many of our favorite stories concern the end of the world through disease or zombies or climatic armageddon. There are wars in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, there is the so-called War on Terror. Even here, in a New York July with no war in sight, it is easy to despair a little over the shortness of summer. It is easy to imagine things ending, and doing so badly. But stories of decline grow tiresome after a while. The truth is that I don’t hope or dream of a terrible ending, not for me or anyone in my family. To defer hope in order to privilege pessimism is an exercise in cowardice and, maybe worse, sloth. It seems to me I would do well to crack another of Bradbury’s short stories, and maybe I would do better to read it aloud in the company of my wife and daughter, to remind us that not only do we not know what the future holds, but that our imaginations belong to the mysteries awaiting us there.

Works Cited

Bradbury, Ray. The Illustrated Man. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1951.

Eller, Jonathan E. Becoming Ray Bradbury. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2011.

Hemingway, Ernest. In Our Time. New York: Scribner, 1996.

Hugh Sheehy’s story collection The Invisibles, winner of the 2012 Flannery O’Connor Award, will appear in October from the University of Georgia Press. He lives in Brooklyn and teaches writing at Yeshiva College.

Purchase the most recent issue (featuring Hugh Sheehy) here!