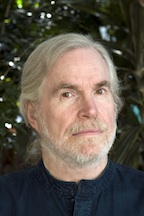

Confab with a Contributor: Edward Hower

by Soniah Kamal · November 03, 20141) Your es say Gratitude, featured in Five Points Vol. 15, No. 1&2 , chronicles the time your family vacationed in Guatemala in 1954 and was inadvertently caught up in the country’s coup. This led to some very tough moral decisions including one involving an ex-Nazi. Why the title Gratitude?

say Gratitude, featured in Five Points Vol. 15, No. 1&2 , chronicles the time your family vacationed in Guatemala in 1954 and was inadvertently caught up in the country’s coup. This led to some very tough moral decisions including one involving an ex-Nazi. Why the title Gratitude?

I discovered as I wrote many drafts of the essay, that the main thing I was feeling for my parents, so many years later (long after their deaths) was gratitude to them both for taking me to Guatemala and then for helping to save my life. Realizing this was a source of both great sadness and exhilaration.

2) Children of the Maze, featured in Five Points Vol. 13, No. 3, is a fascinating journey of the younger you visiting a prison in Jaipur India where you are exposed to inmates such as a Spaniard involved in terrorism, the ‘undertrials’ in prison for years as they wait for court dates, and female inmates whose children remain with them until age six. Having taught English in the American prison system you draw many comparisons between the two systems even as you and your guide come to a startling conclusion about the actual service ‘outsiders’ provide to inmates. If the American inmates and Indian inmates could get together what do you think they would share with each other?

I never met any of the male prisoners in Jaipur except briefly, one of the cooks, so I don’t know how my American prison students would respond to their Indian counterparts. I did assign the essay to my students at Auburn Prison in NY state; they related to the way the Indian undertrials were treated, having been shoved around various holding pens waiting for their own trials, but I doubt if they could really understand the ghastly conditions I observed in Jaipur. I’ve interviewed women prisoners in the US; very few of them had been able to keep children born to them in prison for more than a day or so. So I would imagine they would envy the Indian women prisoners who kept their kids for six years, since trying to keep up with absent growing children was what preoccupied them so much of the time.

3) In Gratitude you eat street foods that are forbidden which leads to all kinds of complications, and in Children of the Maze you accept food by a prisoner which leads to ‘words’ with a warden. Can you talk more about the role of foods as a means to rebellion.

In Guatemala the street food was filthy and caused a lot of sickness among locals, not just dumb tourists. In India, most the street food was great because you could watch it being cooked and eat it right off the little sidewalk braziers. So I was used to eating food like that; the ovens in that prison were flaming hot—no risk, as far as I could see. In all total institutions—the armed forces, prep schools, hospitals, prisons—meals are enormously important in ordering people’s days and dramatically effecting their morale. On rare occasions when people rebel by rejecting food, you can tell that their rage at the institution is unusually intense.

4) Both Gratitude and Children of the Maze plumb the depths of personal morality and collective morality. What are the connections between the two for you? Do you think the world is become a more ‘moral’ place, or not?

Personal and collective morality: we’re affected by collective values and behavior more than we think we are, and people who are able to separate them (like those who protected Jews in Europe during WWII) are unusual and often heroic. I think the social worker in the Jaipur prison was—as I had years before—discovering personal qualms about working in a place that harbored such collective evil. Can one hope to do good in a place of detention where authorities have to harshly repress people’s normal human needs for wanting love and freedom—needs of people who have, many of them, denied their victims the chance to love and be free? It’s very tricky. I think I helped a few of the at-risk kids I worked with, but not enough of them, and I ultimately decided the “juvenile justice” system was too oppressive for me to remain part of. Teaching in adult prisons is different; as a weekly visitor, I can help men gain confidence they need to survive both inside and outside—by helping them learn to use their minds and develop more empathy for the rest of humanity. Education does that, anywhere. Therapy does too, but rarely inside prison walls.

As for the witch temple in India—the collective morality was based on folk beliefs about exorcism which forced me to stop romanticizing folk culture. These beliefs contains wonderful literature and art, but also damage and ex