Featured Prose: Lani Dances the Zombie Hula in LA by Barbara Hamby

by Megan Sexton · November 17, 2011

Lani Dances the Zombie Hula in LA

Lani was standing in the make-up aisle of the Woolworth’s in Hollywood. She hadn’t eaten in six days, and her hands were shaking like two maracas in the fist of an epileptic on amphetamines. All she wanted to do was buy a lipstick, but her mother Ruby kept singing an old Hawaiian song, begging Lani to dance the hula her grandmother had taught her. Okay, to be honest, her tutu was standing beside Ruby, too, gray hair streaming to her waist, and she wanted Lani to sing “Hawai’i Pono’i,” which she’d learned in the fifth grade when they’d run away to Wai’anae and lived in the green Quonset hut on Lualualei

Homestead Road. Lani wasn’t crazy. She knew they were dead, but the voices were so loud she was almost ready to start dancing just to shut them up.

“Mom,” Lani hissed through her teeth. “I’m in Woolworth’s.” But Ruby kept singing, Hawai’i pono’i, nana i kou mo’i, kalani ali’i, Ke ali’i, and Lani felt her feet begin to move over the cracked linoleum of the floor, the rough soles of her feet beginning to speak to the piece of earth beneath her. Sometimes when Ruby showed up, she was fat and drunk the way she’d been at the end, but usually she was young and slim in a holoku with a plumeria behind her ear and a pikake lei, ready to dance at one of the hotels in Waikiki, her hula like the curl of a wave on a moonlit night, with the Milky Way strung over the heavens like the tiara of some giant goddess who ruled Hawai’i before the haoles came with their boatloads of blue eyes and syphillis.

“Lani.”

She jumped and dropped the lipstick. It was a guy with bushy blond curls. He was wearing a plaid shirt and jeans and work boots that were caked with mud. He bent over and picked up the lipstick and handed it to her.

“I know you,” she said, his face coming into focus like an old home movie. It was Jimmy Monroe, not that she really remembered him all that well. It was hard to remember anything when you hadn’t eaten in six days and maybe hadn’t slept in three. Jimmy lived on Lipona Street during the sixties with the rest of the Monroe brood. He was a friend of Lani’s brother Chris, before Chris shot their father and killed him.

“I’m Jimmy Monroe. I lived down the street from you in Honolulu before we moved to ’Aiea.”

Talking was good, talking to anyone. It made the voices go away. Ruby and her mother were fading down the aisle of Woolworth’s, their hips knocking candy bars and tampons off the shelves as they moved in their own zombie hula.

“I remember,” she said, looking down at her bare feet with dirty ragged nails. How long had she been wearing these jeans? And her shirt—it had once been blue. Why hadn’t Marguerite said something? She forgot. Marguerite was mad at her. She was in San Francisco for a week.

“What are you doing here?” Jimmy Monroe said, but he had followed her gaze and was now looking at her feet, too.

“In Woolworth’s?” She put the cleaner foot on top of the other, not that she was fooling anyone. They looked like the feet of a homeless person.

“I was thinking more like L.A.” His face was plain as vanilla ice cream but sweet at the same time. He was just a little taller than Lani, and a little thick around the waist. Lani liked that in a man. She needed something to hold on to, and sometimes a beer belly was all you had in this fucked up world.

“I’m working as a pastry chef.” She turned to the lipsticks and picked out another one. Cherry Madness. What kind of name was that?

“I guess no one’s worrying about you stealing food.”

Lani’s head flew around as though one of the dead people had given it a sharp slap. “Who told you I was stealing?”

Jimmy stepped back until he was leaning between the Maybelline and Revlon displays. “Lani, it was a joke. You don’t look like you’ve had a good meal in a long time.”

“I eat,” she said. “I work in a fucking restaurant. I eat all the time.” She bit her tongue. She sounded rough, like a man itching for a fight, but she was a dirty girl, buying lipstick. How did that sound? How did a woman like that sound?

“Don’t get mad. It wasn’t like I said you were fat. Isn’t that why guys get in trouble—saying girls are fat?”

Lani smiled. “So am I fat or thin?” That was something a girl would say, especially a girl who was buying lipstick, not that she was doing that good a job of it.

“Definitely thin. In fact, so thin that I think I’d better take you out for lunch. There’s a burger place near here where the shakes are great. What you need is a milkshake.”

“Chocolate?” She tried to put the Cherry Madness back in the display case, but she couldn’t roll the new tube back and slip in the tube she was holding. Goddamn it, now even the display cases are conspiring against you, screamed her father. It’s a plot so you’ll have to buy something you don’t even want, never mind need.

“Double chocolate,” Jimmy said, taking the lipstick from her and putting it back into the case next to the other tubes.

Jimmy led her past her screaming dead father and out of the icy Woolworth’s to a beat up Chevy truck, blue with every piece of junk in the universe in the back. Lani almost couldn’t make herself get into the cab, because of the glare of the orange couch in the back.

“Are you moving?” She ran her hand down the orange velvet cushions. It was the ugliest couch she had ever seen, even worse than the mongoose brown living room set in her tutu’s house.

“Maybe,” he said and opened the door and helped her into the high seat. “I’m tired of L.A. I’m thinking about moving to Alaska. They say you can make $10,000 in a couple of months working in a salmon cannery. I want to move back to Hawai’i and buy a little house in Kane’ohe or Waialua. My sister’s husband’s in real estate, and he says prices are going to go through the ceiling.”

Lani settled into the passenger’s seat of the dirty Chevy. Alaska— that was a place she had never thought of going. Canada was the coldest place she’d ever been. She and Marguerite had taken a weekend trip to Vancouver last October. They had eaten dim sum every day for lunch and snuggled up in the hotel room most nights with room service and a bottle of champagne.

Jimmy turned the engine over. It began purring like a big cat at the zoo, a leopard or tiger.

“It sounds like it might make it to Alaska,” Lani said as he pulled out into traffic. “You need to ditch that couch though. Everybody knows orange is bad luck.”

“What color couch would be good luck?”

“White but it’s not really practical when you’re thinking about driving a thousand miles.”

“It would be grey by Seattle,” Jimmy said, his smile like a hibiscus opening after a morning rain.

“And then your luck would be gone,” Lani said, turning away from him to the broken down buildings speeding by. Once people ate lunch there or bought magazines, and this was where movie stars had been discovered. You wouldn’t find anything now but some broken down winos or rats. That’s the way it went.

Lani didn’t need Jimmy Monroe’s smile, but maybe she needed his milkshake, so she sat in his dirty truck like the good girl she’d never been and waited for him to take her wherever he was going.

Pretty soon they were in a booth at a little diner on Sunset. Jimmy was eating a burger and fries, and Lani was sipping a chocolate shake as if it had to last her for the rest of the week.

“How’s the shake?” he asked, looking at her as if he were some kind of bug collector looking at an especially juicy specimen through a microscope.

“Hey,” Lani said, “I know I look bad.”

“Are you kidding? You couldn’t look bad if you tried. I always had a crush on you back on Lipona Street. I can’t believe I’m actually sitting across the table from you. How long have you lived here? I didn’t know you were in L.A.”

Jesus. How was she supposed to answer all those questions? Crush. What was he talking about?

“Can I get some water?” Lani said. The shake was turning sour in her mouth, or maybe it was her mouth that was sour. She reached for a napkin and pretended to wipe her lips while spitting the mouthful of icy chocolate into the napkin while Jimmy turned to signal the waitress.

“You can have mine,” he said, pushing his glass across the table to her. “I haven’t touched it.”

Lani gulped the water like a drowning woman, which, in fact, she was. She knew it, but that didn’t mean she could start doing the breaststroke or even float on her back until the lifeguard showed up.

“Hey, you were thirsty,” Jimmy said, eating the last of his burger. “Do you want some of these fries?”

Lani felt the ball of water, milk, and ice cream rise in her throat like a hand pushing up from the bottom of the ocean. She bolted back to the rest rooms and threw up in the toilet. The water had been too cold. If she hadn’t drunk the water, she would have been fine. Why did she eat anything? It was always the same. She sat on the toilet and thought about the trap she was in. Number one: She couldn’t get out of the restaurant without walking past Jimmy Monroe, who was sweet, but made her stomach feel as orange as that ugly couch in his truck. Number two: when and if she could get away from him, it was a long walk home, maybe six or seven miles. But she didn’t mind walking.

Two months ago she’d left her car on a street in Santa Monica and walked home. It had taken her two days, but she’d gotten sick of being a taxi for her dead family. They piled into that Toyota and yelled and screamed and whined and sang, until she wanted to drive right off a cliff into the ocean. Her father and Ruby had been screaming in the back seat when she parked the car and left it with the key in the ignition. She loved walking because, they were old and dead, so she could outpace them—no problem.

But that still left her with Jimmy Monroe. She opened the stall door and looked at herself in the milky mirror over the sink. Even skinny and strung out, she looked good. After all she was Ruby Kaapuni’s daughter. Her face was long and narrow like her father’s, but she still had Ruby’s creamy skin, her dark liquid eyes, and the waterfall of brown hair, Polynesian despite the haole taint, despite the Kentucky backwoods boniness of her father. She was surprised she hadn’t slept with Jimmy Monroe. She’d done it with so many guys from the neighborhood. One time she’d been at a party and realized she’d slept with every man there. It wasn’t that big a party—maybe seven or eight guys, but it was weird. Well, whatever she’d done in the past, she didn’t want him now. Marguerite was taking care of her.

Outside the ladies’ room, she stood in the vestibule. She needed a plan to get rid of Jimmy. Maybe if she just walked past him, she could outrun him when she got outside. He’d have to pay the bill, which would give her about three or four minutes. But what if he just threw the money on the table? She wished she’d paid more attention when they’d parked the truck. Raymond Chandler she was not.

Then she saw an alcove at the end of the vestibule—the fire exit— and she didn’t break her stride, pushing open the door and running out into the alley behind the restaurant, the fire alarm clanging before the door shut. Lani didn’t look back but ran across the hot asphalt of the parking lot, her feet too dirty and calloused to feel the heat rising from the black tar. She ducked behind a hedge of oleander and found herself on a leafy street of small apartment buildings and old bungalows. Running across the street and through another alley between buildings, she hid behind a green dumpster, peeking over the top from time to time to see if Jimmy’s truck was coming down the street. After about twenty minutes she found a low bush, and curled up beneath it and watched the light play through the leaves.

Though it started softly, a song of Pele and the other gods began to waft around the bush, her tutu singing the way she had when Lani and Chris were kids and their mother had dropped them off to go on a bender.

Mai Kahiki ka wahine o Pele,

Mai ka aina i Pola-pola,

Mai ka punohu ula a Kane

Mai ke ao lalapa i ka lani

Mai ka opua lapa i Kahiki.

She’d sing them to sleep with old Hawaiian songs. Lani closed her eyes. She didn’t want to see her grandmother, but the song filled her like a big bowl of saimin, the noodles soft and warm. She was asleep when Jimmy’s truck passed on the street thirty feet away.

The chill woke Lani, and it was dark. What time was it? Eight? Two? She was cold. Rubbing her arms, she sat up and bumped her head on the branch of the bush. For a few seconds she thought she was in the back yard of their house on Lipona Street, in the pup tent with Chris, trying to get away from their father beating Ruby, and then the inevitable reconciliation when they would shake the house with their lovemaking—Ruby screaming like a cat in heat. She must have been faking it, but maybe not. Sex was funny. God, that’s one thing Lani knew for sure, how you could love and hate a man at the same time, him lying there on top of you, a god one minute and an animal the next.

On the street Lani tried to remember where she was. Oh, right, Jimmy Monroe—he’d probably given up hours ago. She walked towards the sounds of car horns and engines. Jesus, what day was it? Was she supposed to be at work? She had a quarter in her pocket. Maybe she should call the restaurant, but she was afraid that they’d say yes, where are you, the profiteroles aren’t made, the lemon tart is lemon soup, the clafoutis is just a big pile of fresh cherries. Jesus, how long had she slept? It felt like a few hours, but it could have been days or weeks or months. Maybe it had been years. That was it. She was Sleeping Beauty just up from her 100-year sleep. That would be the answer to her prayers. Her father and Ruby would have dropped from Purgatory to Hell in that time, and Lani was sure the schedule was pretty tight in Hell. They wouldn’t be out walking the streets on a day pass.

When she got to Sunset, a shiver shot up her spine, and she could feel her own personal posse of zombies coming up behind, the rustle of their feet, the murmur of their voices, each with its own complaint like a trio in an opera by a Bizarro Mozart. As she set off down Sunset, she remembered using flashlights to read Superman comics with Chris while their parents acted out their tawdry opera in the little house ten feet away, beyond the wall of ginger and papaya trees. She was at the corner of Sunset and Sweetzer. It wasn’t really that far from her apartment. She’d be there in a couple of hours tops. She loved walking on Sunset. There were so many people that she wasn’t scared. The only bad thing was when she passed a restaurant. The smell of the food was like a forearm down her throat, but that was the great thing about being a fast walker. She could race past a restaurant in less than thirty seconds. What did Jimmy Monroe want anyway? Why had she gone with him to that stupid restaurant? A milkshake. For God’s sake, she hadn’t had a milkshake since she was seven.

Lani was concentrating so hard on outrunning her ghosts that she didn’t hear Jimmy Monroe’s truck pull up beside her.

“Lani,” he called.

She stopped as if frozen by an alien’s stun gun, but she didn’t look over at him. She could probably run for a while, but what then? She could feel her father rubbing up against her back, hand reaching for her breasts.

“You didn’t have to run away.”

She stood like a statue on the sidewalk. Why did she have to talk to this idiot? Just because they lived on the same street in Honolulu? Why wouldn’t he disappear? If it weren’t for her father and mother, she’d make a run for it, but they were surrounding her like the Sioux in an old Randolph Scott movie, only the Sioux had not been shouting, Run out into the street. You can get away from him. Just run out in front of that car. You won’t have to talk to anyone again. Hawai’i pono’i, nana i kou mo’i.

“Take me home,” she said to Jimmy and ran around the car and jumped into the passenger’s side of his truck. Boy, that surprised them.

Her father, tutu, and Ruby were standing on Sunset like a group of retards on a field trip.

“Where do you live?” he asked.

“Drive, goddamn it. I’ll give you directions later.”

He gunned the engine and peeled out. She looked back. Ruby, her father, and her grandmother were standing on the sidewalk by the Whiskey a Go Go, her tutu in a muumuu, strumming a ukulele, like some kind of big fat Hawaiian tourist attraction. Lani slumped back in the car and closed her eyes. She couldn’t keep running and not eating. Marguerite was sick of her, and Lani didn’t want to go back to the hospital.

They’d just shoot her full of Thorazine, and then she’d be a zombie herself. Half-dead was worse than dead, because you were awake enough to know you were a corpse.

She looked over at Jimmy Monroe. He was staring straight ahead. What could she expect from him? Well, he’d driven around for a couple of hours in his truck looking for her while she took a nap under a bush.

“Listen,” she said. “I’m in trouble. If you can’t help me, just drop me off at the hospital. I can’t eat, I can’t sleep, I can’t work, I’m hearing voices. I’m going to kill myself if you don’t help me.”

“What can I do?” he said.

“Take me to Alaska with you.”

He looked over at her. She could see the wheels turning behind his vanilla ice cream haole forehead.

Lani knew how he felt. Where had that come from? But the more she thought about it the more she liked the idea. Los Angeles was part of her problem, the job at Marguerite’s restaurant, the grid system of the streets. It was too easy to get around, and her father and Ruby could follow her trail through the smog. Even though she didn’t eat, she gave off this baloney stink that lingered in the heavy metal of Los Angeles. In Alaska the air was clean. She wouldn’t leave a trail there no matter how bad she smelled. And she bet the roads were crooked. Those three old farts wouldn’t know what hit them. She looked over at Jimmy Monroe driving his Chevy and smiled at his soft face. She could make him want her. She would have to start eating. It was always hard to start again after she’d stopped, but she could do it if she had to.

“Turn left on Doheny,” she said. That’s what she needed—clean air and some turns in the road. But what about Jimmy? Yeah, he wanted her, but did he need that much trouble in his doughnuts-for-breakfast life? Who did? If he had any sense, he’d run screaming to Alaska and gut salmon until he gathered his stash and was able to hula on back to O’ahu to buy his little termite shack on the North Shore.

Lani was counting on him being a little stupid about sex. Most men were. She could do that fake hula in her sleep. She could get up in front of the tourists and swing her hips to “Lovely Hula Hands” and make

them think they were seeing the real thing. She’d been doing that hula since the first night her father slipped into bed with her, Ruby drunk in some bar in Waikiki or Kalihi, losing her beauty in the acres of flesh she was building around whatever was left of the Hawaiian girl who met the haole officer after the war. Her parents’ story was like a fairy tale but one where the witch baked the two kids up good, roasted their tender little asses and served them up with new potatoes, French-cut green beans, and a big three-layer chocolate cake.

When they got to Lani’s apartment, she flipped the switch but no lights. Shit, she’d forgotten to pay the bill. Marguerite was going to kill her. Where was her purse? She had seven hundred dollars in her wallet. In the moonlight from the kitchen window, she saw it on the table. She turned at the door and waved him away.

“I’ll be okay,” she said. “I need to sleep.” Fat chance—that nap under the bush was the first time she’d slept in days, which meant she probably wouldn’t sleep again until February.

Jimmy was standing on the sidewalk like a mendicant friar, his hands clasped in front, legs planted about a foot apart. Or maybe he was a paramilitary operative standing ready to storm her fortress. Lani had no way of telling. She tried to remember how she used to think when she could eat and sleep. So she said nothing and walked into her apartment, leaving the door open, and lay down on the couch. He followed her and closed the door. From the corner of her eye his shadow moved across the room to a guitar that was propped against the wall.

“Is this yours?” he asked and picked it up, strumming it.

“No. I don’t know who it belongs to. One of Marguerite’s friends.” This was a lie. She could remember the guy’s face but little else about him except he’d bought her drinks all night, one right after another like little soldiers in a battalion trying to liberate her mind from its jail.

Jimmy sat on a yellow vinyl kitchen chair by the television and began to tune the guitar, and in a few minutes he was playing something classical, the notes scattering over the dark room like a swarm of fireflies escaping from a jar. Lani felt as if ice were cracking over a hot sea in her chest. She lay on the couch, breathing in the notes that flew from Jimmy Monroe’s fingers, the little sparks cascading through her like food and drink, and she remembered him as a skinny boy with a wild thatch of blond curls, quiet, looking down at the ground. When had he learned to do this, make notes careen through this dark room, so real you could almost see them?

After the Bach—it had to be Bach—he started on Bob Dylan. He was playing one of Lani’s favorite songs—“Love Minus Zero, No Limit”—from Bringing It All Back Home, but his low voice softening out the lyrics like a martini that was equal parts Dylan and Dean Martin, the half-remembered words coming back to her like old friends, until at the end of the song she was that raven with a broken wing. If he’d stopped there, she could have gone back to her job the next day— pitting the cherries for the clafoutis, whipping the cream for her famous banana coconut cake, curling the chocolate for her double rum torte— but he kept playing—Tim Buckley’s “I Must Have Been Blind,” Johnny Cash’s “Long Black Veil,” Billie Holliday’s “God Bless the Child”—until the early sun sneaked in between the slats of the blinds over Marguerite’s living room window. By that time her ghosts were in Timbuktu, and she would have gone with Jimmy Monroe to Outer Mongolia just to hear him play “Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring” before she went to sleep each night, because she finally did sleep—ten hours of deep, dreamless darkness—so that when she woke and he took her out to an all-day breakfast place, she was able to eat two blueberry pancakes, a poached egg and bacon, and drink a glass of milk. Later that day they put the orange couch on the side of the road and piled everything Lani owned into the back of his Chevy pickup. They drove northward singing “I Ain’t Gonna Work on Maggie’s Farm No More,” “Born to Be Wild,” “Sisters of Mercy,” “I’m in Love, I’m All Shook Up.”

When she forgot the lyrics, it was okay, because Jimmy knew them all, just as he could read the map of the knotted highways of California, Oregon, and Washington that looked more like the veins in the arm of a heroin addict than a plan of the highway system that would take them through the small towns and big cities along the Pacific coast.

Jimmy moved through the world as if there were no detours, no dams, no brick walls so thick even a wrecking ball couldn’t penetrate them. His world was made of water, and even though the people they met couldn’t know about his music, they acted as if they did, because there was music in his voice and in his hands and in his smile. Even waitresses were kind to him, hardbitten women with plastic nametags that said “Edith,” “Lurleen,” “Dot,” women who had seen their share of dead ends and stop signs if the maps of their faces were telling the truth.

Lani marveled at how he’d find the right motel or campground, how his fingers moved over the guitar strings as he practiced every evening. Sometimes she would dance, barefoot in the motel room, her long feet clean, with trimmed pearly nails, following the rhythm of his song. She loved his voice, the way it moved on the air like some radio broadcast from another world with none of the wild animal screams that came from the regular zoo of zombies that stalked her through the streets of Honolulu and Los Angeles. She hadn’t seen her father or Ruby or her tutu since Jimmy had picked up that guitar, but she knew they weren’t gone. They were probably following on a Greyhound bus, their screaming scaring the migrant workers, teenagers driven away by angry stepfathers, or poor single mothers with black eyes running from the men who would one day kill them.

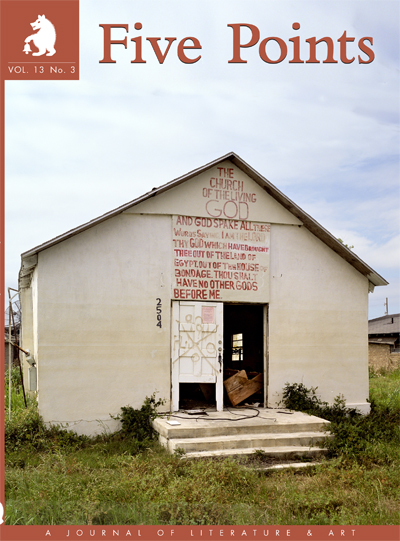

Published in Five Points Volume 13.3.