Featured Prose: The Pound Game by Mick Cochrane

by Megan Sexton · May 05, 2012

The Pound Game

Wilson does not sing simple songs. This woman is reading from something, it is a thick official document, an assessment, she calls it, but the tone is judgmental, accusatory. An indictment is what it is. Her name is Ms. Biondi. She is a therapist, a clinician, her name followed by a long series of initials, unimaginable degrees. She reads quickly, relentlessly, without affect, measuring his son’s deficiencies on various hyphenated scales, delays measured in percentages and calculated to the second decimal. The boy is four years old and slow to speak; he’s sometimes difficult to understand. But as Ms. Biondi reports the results of her testing, the problem is more complex, more vast. She recites a long litany of ordinary milestones not met—cognitive, social, syntactic—accomplishments not achieved, but just that one sticks, worms its way into his consciousness where it sticks like a fishhook in his heart. Wilson does not sing simple songs.

Fred had foolishly imagined something else entirely, a different kind of proceeding altogether, something cooperative and supportive, sympathetic, possibly therapeutic, chairs pulled together in a semicircle, Styrofoam cups of coffee, knees almost touching. But when Fred explains that his wife will not be able to attend, that she is in the hospital, the response is so muted, he feels as if he’s breached decorum somehow, been inappropriately personal, offered too much information.

In fact, this seems like some sort of quasi-legal procedure, six or seven people with titles arranged behind a long table. Somebody from the school district, a parent representative, the coordinator of special

education, a small squadron of therapists. They have nameplates, reading glasses, thick stacks of files in duplicates, water glasses. It’s like a senate hearing.

They’d done the tests—a battery of them, they called them, administered a day-long beating—two weeks before at Children’s, spent the better part of a day moving from department to department, from office to office. It was hot and the air conditioning was on the blink. There were doors and windows propped open with books and brooms, the receptionists all sweaty and fanning themselves with manila file folders. The tests were administered in rooms the size of broom closets, all by different specialists, each of them abrupt, professionally cheerful in a too-loud, vaguely menacing way. If you got in Wilson’s face right away, demanded to shake hands and peppered him with questions, he shrank, hid, buried himself behind his father’s legs. He performed part of what seemed to be some sort of I.Q. test from beneath a chair, reaching out gamely to match shapes and colors, his little knuckles dimpled with baby fat. Fred should have put an end to it then. There were more tests, but Wilson had had enough. There was some coaxing, then bribes, finally threats. Eventually, flushed with the heat and utter frustration, Wilson kicked a chair.

“Such anger,” the psychologist said. “Where is that coming from?” she asked Fred. The implication seemed to be that it was coming from him somehow, that he must be the chair-throwing type. He’s not; he’s pacific, probably to a fault. He retrieved the chair and apologized on Wilson’s behalf, but deep down he more than understood, he cheered—under the circumstances, throwing a chair struck him as a deeply honest, utterly sane response, the definitive right answer.

He could try to explain, but where would he even begin? “I don’t know,” he told her, “I’m not sure where that’s coming from,” and she made a notation on her clipboard.

The case against Wilson is air-tight. He is speech-impaired, in need of Special Services. Various therapies are recommended, speech, occupational, several others. The word he keeps hearing is “intervention.” The importance of early intervention, various intervention strategies, multi-faceted interventions. As if his son is a third-world country they’re planning to invade, a tumor they intend to

remove.

The man from the school board, silent up until this point, finally speaks. He is silver-haired, with a neatly trimmed moustache, and the faintest accent, vaguely but not quite British. He has the smiling air of an elected official, which he apparently is. He explains Fred’s options as a parent, his rights, so slowly, with such rehearsed scriptedness, Fred realizes, this is some sort of Miranda speech, a safeguard against

lawsuits. Fred reads the man’s name—Robert Blum, Jr. and tries to memorize it, like a license plate, in hopes that he’ll someday have the opportunity not to vote for him.

Fred is profoundly distrustful of bureaucratic machinery of any sort, suspicious of the district’s supposedly benign concern—he’s been a union rep, he knows how they operate—not at all sure that he wants Wilson to be classified, to be brought, in their words, “into the system.” In a phrase like that, he can practically hear the clanking of the chains, the key in the lock.

Things conclude somewhat vaguely—papers to be read and signed, a learning plan to be drawn up. Any questions? If Martha were here, she’d have questions, Fred is sure of that, some pointed questions. That’s her job, asking tough questions, in depositions, in court, thinking on her feet. The things he thinks of afterwards, she says at the time. Fred is by nature slower, more deliberate. He likes a lesson plan. The more detailed the better, whether he looked at it or not, it made him feel secure, knowing it was there. Now he lives in the land of no lesson plans, and he’s learned simply to listen and nod and wait. There’ll be time to talk it over with Martha later.

He stands and thanks these people, people for whom he feels no gratitude, because . . . because that’s the kind of man he is—the deeper he feels himself in trouble, the more polite he becomes. He’s thanked a state trooper for a hundred-dollar ticket. Shaken hands with the doctor who found his wife’s cancer.

Back at the hospital, Martha is propped up, IV’d, slurping soup, watching Andy Griffith on the overhead TV.

“Goober thinks his dog can talk,” Martha says.

She is still pale, but no longer frighteningly so. The day before, when they’d signed her in, her blood pressure was dangerously low, barely registering. She’d put Ellis on his bus, come into the house, and blacked out. Upstairs in the bathroom, Fred heard a sickening thump and found her sitting on the pantry floor, groggy but game, like a heavyweight who didn’t want the fight stopped, protesting she was fine, just fine.

Fred picks some saltines from her tray and takes a sip of her water. He looks at the television. Sitting on a stoop with a scruffy-looking shepherd mix, Goober is grinning from ear to ear. Fred remembers this episode; he’s seen it before—it’s just Opie and a new kid in town

pulling a prank. They’ve got a walkie-talkie rigged to the mutt’s collar. Andy will teach the boys a lesson in the end, but still, it makes Fred sad to see Goober so pathetically duped.

She fills him in, the results of her blood work, which is basically good, fine, fine, nothing much beyond the normal chemo response. If her antibodies come back just a little, she’s good to go again next week. But once again, there seems to be some fluid accumulating. Not a lot, nothing to be alarmed about, that’s what they keep saying. Her scan was clean.

So why? Fred wants to know. But the doctors don’t have any definitive answers. Maybe this, maybe that. Maybe nothing. Maybe they don’t know what the hell they’re talking about, he’s tempted to say.

He wants some certainty. All the high-tech machinery, the journals piled in their offices, the white coats. They look like scientists, but they talk like somebody’s farmer uncle chewing the fat about the weather. Could be. Hopefully. Probably. Wait and see. Fred’s car mechanic can diagnose a squeak or a sputter with much more confidence.

“How’d it go?” Martha wants to know.

“Okay,” Fred tells her.

“That bad,” she says.

“Wilson is speech-impaired,” he says. The official language sounds

foreign in his mouth.

“It’s going to be all right,” she says. “We’re all going to be all right.” Fred isn’t sure what that even means, he cannot imagine what “all right” might look like, but he nods.

“It was like a trial,” Fred says. “It was like he’s guilty of something.”

“I know,” Martha says. “I know.” For now neither of them says anything more. There’ll be time to unpack it all later. He takes her hand, gives it a slow massage, rubs her wrist under her hospital bracelet. She’s out of gas, and he’s sorry that he’s tired her out. They have a sad moment of silence together, watching the Andy Griffith closing credits on the television screen.

She taps her wrist and jerks her thumb to the door. “Now get going,” she tells him. “They hate it when you’re late.”

Fred offers to stay. He can call a neighbor to watch the boys, but Martha insists he do it himself. They’d agreed to stick as much as possible to their family business as usual—“keep it normal” is how Martha puts it. Which is absurd, of course. But they do it anyway. They try their best.

In the preschool’s parking lot, Fred straps Wilson into his car seat. Asks him about his day and receives the usual answer. “Good.”

“What was snack?”

“Red juice,” Wilson says softly. “Circle crackers.”

Fred can understand him perfectly, goddamn it. If you just listen, he’s 100% intelligible. Wilson looks out the window, watching serenely, and his father tries to follow his line of sight, imagine what he’s observing— sunlight through the leaves? If you love someone, you can understand them. If you don’t, you can’t. How hard is that to grasp? You need a graduate degree to figure that out? That’s something Fred might have told Robert Blum, Jr. and his team of so-called helping professionals.

When Fred picked him up, Wilson had been playing with his new buddy, Cheyenne, digging through a sand pile for small brown stones, which Wilson has been bringing home in his pockets all week, insisting they are magic beans. They do look a little like beans, brown and smooth. Some seem to have a little cleft, like a coffee bean. He’s been finding them between the cushions of the couch, in Wilson’s bed, in the washing machine. Fred stood for a moment, out of sight, and watched Wilson and Cheyenne work in perfect wordless cooperation.

One of the few jokes Fred could remember long enough to repeat involved a little boy who never spoke, not for years, not a mumbling word. Finally, finally, after many years, at the age of nine or ten, the kid breaks his silence. “Mom,” he says one morning. “You burned the toast.” The family is astonished. Why? they wonder. No words all this time. “Up to now,” he tells them, “everything’s been fine.”

Fred starts to sing. If Ms. Biondi wants simple songs, he can do simple songs. It’s been an oversight, easily corrected. “Row, row, row your boat, gently down the stream…” He sings it through twice. No response from Wilson. He tries “This Old Man.” He makes it all the way up to five, knick-knack on my hive, which doesn’t sound right. Hive? But he can’t think of anything else that rhymes with five; it must be hive. And what in god’s name is knick-knack? On a hive? It sounds obscene. He can’t believe this is a children’s classic. He sings louder now, brings even more forced joviality to his performance—he is a happy scoutmaster, he is Miss Betty, he is Raffi in concert. He plays knick-knack on his gate, on his spine. He looks and sees Wilson in the rearview mirror. The boy fixes him with a look that seems to express both bewilderment—what is with you?—and betrayal. You too?

At the kitchen table, while Wilson stands on a bench at the sink, scrubbing his soccer ball, for the second or third time today—he’s the neat and clean one, give him a bottle of Windex and a roll of paper

towels, and he’s in hog heaven—Fred sorts through the contents of Ellis’s backpack. His lunch is mostly uneaten, save for his cookies and one perfect bite from his cheese sandwich. The apple has been back and

forth more than once and is looking the worse for wear. Ellis has a good appetite; he’s just the slowest eater his father’s ever encountered, a talker, a dawdler, who may not even get around to picking up a fork for a good ten minutes. The lunch period at his school lasts something like eighteen minutes.

“How’s Mom’s blood pressure?” Ellis asks, and Wilson pauses in his ball washing operation. His hearing is perfect. This is not the sort of conversation Fred thinks he ought to be having with a nine-year-old, but Ellis is an unusual kid. He hears everything, remembers everything. He’s always been full of questions, and Fred has always tried to give him straight answers, not to blow him off.

“Good,” Fred tells him. “Excellent.”

“How’s her electric lights?”

“Perfect,” Fred says. “They’re blazing.”

Still, Ellis looks worried. The week before, he had accidentally walked through the downtown library’s security gate with a book. An alarm sounded, and while the uniformed security guard, smiling the whole time, disengaged it, Fred could see the color drain from his son’s face. He held back the tears until they made it to the car. “The same thing happened to you once, didn’t it, Dad?”

“Sure,” he said. “It happens to everybody.”

“Tell me about that time,” Ellis said, and Fred cooked up some bogus parallel narrative, a fiction involving himself, his own father, a library, and a security guard. Of course, books weren’t electronically

tagged back then, and he’s pretty sure his father never set foot in a public library, but no matter, the point, he figured, was not the details but the reassuring noise of his voice. Has Ellis always needed so much reassurance? Fred doesn’t think so.

“What time tomorrow is Mom coming home?” Ellis asks.

“The doctor says first thing in the morning,” Fred tells him. “She’ll be here to meet your bus tomorrow.”

“What if she’s not?”

“Then we’ll be disappointed,” Fred says. Politicians never answer hypotheticals, and now Fred understands why: his kids, Ellis and Wilson both, can fire off a half dozen or so in a single volley, what about this, what about that. Fred has his own hypotheticals, half-formed, dark rooms he doesn’t want to visit. “But look,” he says. “They said tomorrow.”

“If not,” Ellis wants to know, “can we sue them?” Lately he’s terribly interested in the idea of lawsuits and litigation: liability, what companies do to avoid being sued, all those little disclaimers in fine

print—what is sold separately, not included, not actual size, the fact that color may vary and contents may settle during shipping—the rationale for release forms and permission slips. He’s dying to sue somebody, anybody.

“I don’t think so,” Fred tells him.

Fred has tried to explain the notion of damages, how fault is proven and priced out, but it’s hopeless. Ellis wants to sue Crackerjack because his prize was broken, KFC because they ran out of biscuits, the Cartoon Network because of technical difficulties. Fred sympathizes with the desire, he understands the urge. He understands his son’s wish to be compensated for disappointments, daily sorrows, all the broken promises spewed out by the fast-talking, bait-and-switch world.

“Rats,” Ellis says.

“How about we sue somebody else?” Fred asks.

“Like who?”

“Like the lunch ladies.” Martha would give him hell for planting such an idea, but Fred sees Ellis’s eyes light up, the joyous sense of possibility—justice, revenge, a big windfall at a crabby adult’s expense.

“For what?” Ellis wants to know. “What could we sue them for?”

“Meanness,” Fred says. “Ugliness. Are they ugly, too?”

“Oh yeah,” Ellis says sadly, knowingly. “But you can’t really sue for ugliness and meanness. Can you?”

After dinner, once the boys are pajamaed and their teeth brushed, he agrees to play the pound game, a quick round. They are dogs, strays, housed in a kennel beneath the dining room table. He arrives at the shelter in search of a pet and brings them both home. It is a kind of fairy tale they enact, again and again, some canine Cinderella story, the adoption motif complicated with almost infinite variation.

Each boy fixes his dog-identity—breed, color, size—only after a great deal of deliberation, a certain amount of negotiation, lots of last-minute changes. Ellis is a Husky named Howler. He is part wolf. Wilson is a black Lab pup named Blackie, no, a Dalmatian named Spot, actually, a chocolate Lab named Labby—Ellis rolls his eyes and starts to complain, “You can’t just . . .” but Fred shushes him—then Brownie, then, at last, Chip.

While they conceal themselves under the dining room table, he shows up at the shelter and gives a little speech, announcing his desire for a couple of good dogs, wondering aloud what he’ll find. If he goes too far off script, if he doesn’t say it right, the boys make him start again—it’s some sort of incantation. He coaxes them out, and they bark and yip and growl, and as necessary, give him instructions and feed him new narrative details in a kind of stage-whisper. “At first,” Ellis says, “you think I’m a wolf.”

He looks into their mouths to examine their teeth, inspects their paws, checks their noses and pronounces them wet and cold. They perform a few quick tricks. Wilson/Chip shakes his hand, a hearty, smiling squeeze, human-style, worthy of a photo-op. Ellis/Howler rolls over, turns a quick somersault, and plays dead, hands-paws crossed across his chest.

Fred wonders aloud how much for both dogs. “Sixty dollars,” Ellis says. “Sixty hundred dollars,” Wilson says. In the end, he pays six hundred, and lays out six imaginary bills on the table.

“Okay,” he says. “Time for bed.”

Who knows what this is all about, their inexhaustible enthusiasm for this game. He believes boys, his boys anyway, are pack animals. He’d said so once to a woman at a playground, and she’d edged away from him, appalled apparently by the idea, by anyone who could entertain it. Maybe she was the mother of girls, a couple of those fine-motor geniuses who drew flowers for hours on end. He knew the type. He used to see them and marvel when he’d pick up his own boys at pre-school: they’d be coloring or primly braiding hair, wearing headbands and ribbons and adorable dresses, while the boys would be charging around in the back with capes and makeshift swords, playing Robin Hood.

But it’s true. Ellis and Wilson have always rolled around on the floor together, roughhouse-pouncing themselves breathless. Wrestling is probably Wilson’s favorite form of human interaction. Fred used to worry about injuries, try to step in and break it up, send them off to neutral corners. But now he’s seen it on the Nature Channel—it’s cub behavior.

“Heel,” he says, and they follow him up the stairs on all fours. “Kennel up.” It occurs to him that they obey him much better as dogs than they do as children. Maybe he should lose the parenting books—

there’s a bunch of them on his nightstand, under the cancer books, all unread—and focus on dog training. Another appalling insight into child-raising that he knows he’d better keep to himself.

Twenty minutes later, Fred—sitting on the living room couch, the paper on his lap, a muted ballgame on the tube, wondering whether or not it’s too late to give Martha a call—hears the boys upstairs, some furtive footsteps back and forth between their rooms. It sounds like mischief. He climbs the stairs as far as the landing; he can see the two of them in the bathroom, their backs to him, conspiratorially busy, definitely up to something. Ellis is standing on the closed toilet seat, holding Wilson’s plush Wild Thing in one hand, reaching up to the shelf for something. Fred is just about to holler at them when he figures out what Ellis is doing: he’s dousing his brother’s stuffed toy with Martha’s Estee perfume, the scent she’s worn for years, performing a little spraybottle baptism. “There,” Fred hears Ellis say to Wilson. “Smell that.” Wilson buries his face in the toy, Ellis grins triumphantly, and Fred backs quietly down the stairs.

When Fred awakes in the middle of the night, there is someone looming over him, a face leaning into his. It is Wilson, naked, standing at the side of his bed, clutching his Wild Thing. “What’s the matter?”

“Somebody peed in my bed,” Wilson says softly, eyes downcast.

“Don’t worry about it,” Fred tells him. He lifts the comforter and Wilson scrambles aboard.

Fred sleeps fitfully and wakes again at dawn—there’s just a little light coming in the window. Ellis is in the bed now, too, lying across the bottom. It’s like they’re on a raft, the three of them, some cramped, makeshift, lashed-together affair, like Huck and Jim’s, headed downstream together. Ellis is sound asleep but his jaw is working slowly back and forth, making a terrible grinding. The sound is so insistent and destructive, it scares Fred. Where is that coming from? the social worker would want to know. He’s had nightmares about skeletons, he’s confessed to Fred: like the shipload of ghost pirates he saw in a trailer for a Disney movie, eyeless sockets, grinning, dancing.

Fred doesn’t want to wake Ellis but he massages his jaws a little, rubbing slow circles in his clenched jaw muscles, talking to him a little. “It’s okay, pal,” he says. “Everything is going to be all right. There’s nothing to worry about.”

In the bathroom Martha’s perfume bottle is still on the edge of the sink. Fred sprays some into his palm and inhales. He looks at himself in the mirror: he’s as unkempt and disheveled as any Wild Thing.

On the floor he finds Wilson’s wet pajama bottoms and one of his

magic beans. Fred picks it up and rolls it in his palm. It feels as if there’s no magic in it, no magic anywhere. There’s no such thing as a talking dog. Don’t be stupid, he tells himself. It’s not even a bean at all. It’s a stone.

He knows better. But he does it anyway. Nothing seems strange anymore. Closes his eyes and makes a wish. Like a child, like a damn fool.

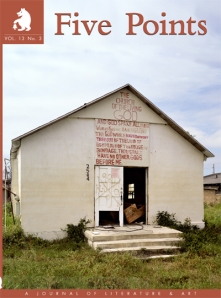

From Five Points Volume 13.3