Interview: Maud Casey on CITY OF INCURABLE WOMEN

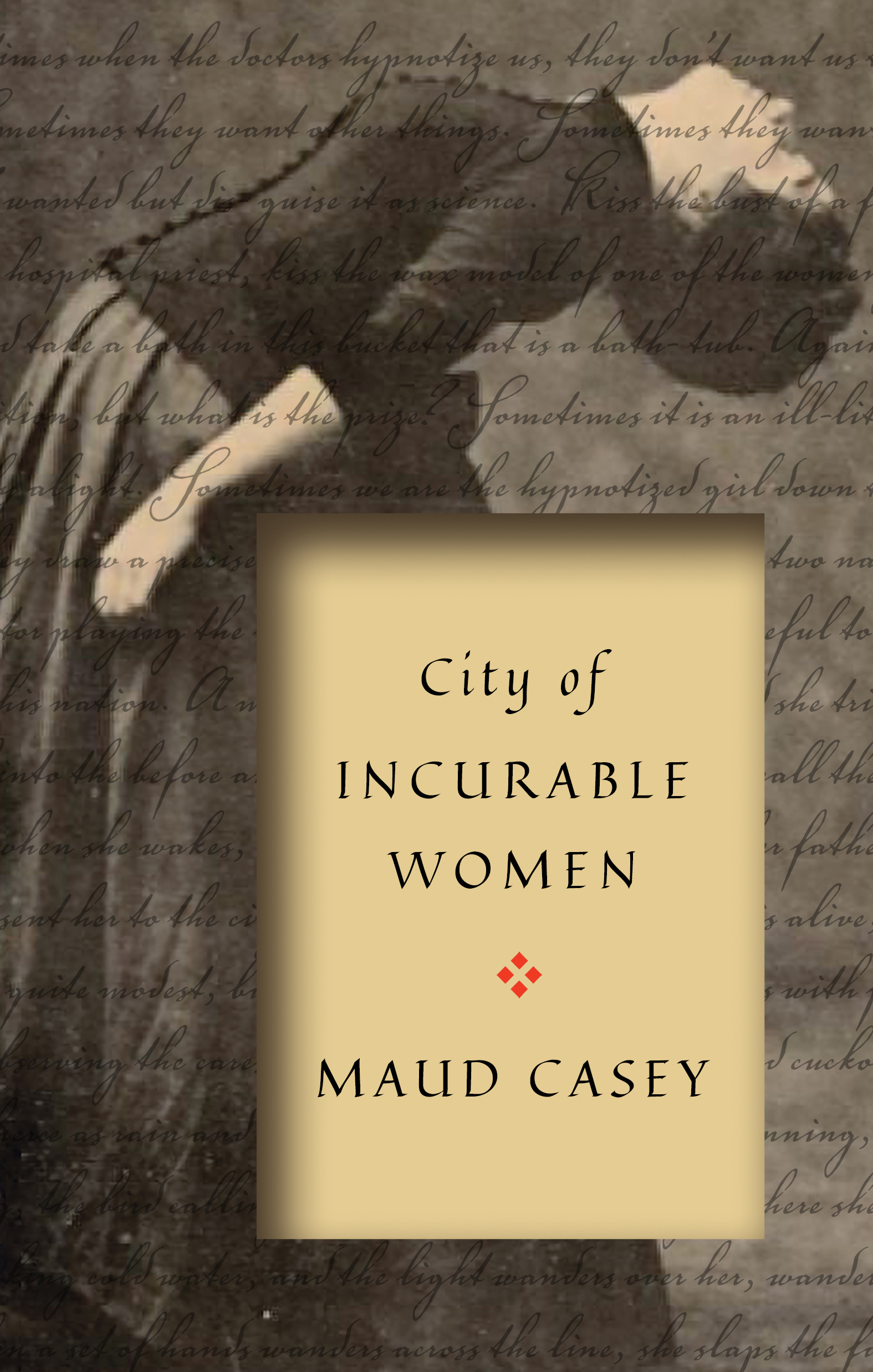

by Jada Ford · April 20, 2022City of Incurable Women by Maud Casey is a symphony of words and photographs; in the following interview, the author discusses her writing process, the history within fictional imaginings, and the girls who lived in the Salpêtrière hospital.

“The best girls are fluent in the language of their pain,” writes Maud Casey who has re-populated the historic streets of the City of Incurable Women. When asked to define what it meant to be “fluent,” Casey stated, “It’s safe to say the women and girls who arrived at the Salpêtrière learned this language [of pain]. There were photographs of them performing various stages of hysteria throughout the hospital, among other things.”

Published in Volume 19.2 of Five Points, Casey presented “A Heartless Child,” which also features a shared perspective. In this recent book, the shared perspective holds a conversation with the disconcerting (and deeply poetic) voices of the women institutionalized in Paris’s Salpêtrière hospital. Their testimonies are extremely effective, as if Casey found an echo of their voices lingering in the hospital, and she pairs these echoes with documents written by the predatory doctors. The end result is a brilliant cacophony of perspectives that unveils the following: “We humans are mysteries to each other, and even to ourselves. Our pain, the exact nature of it, is a mystery” (Maud Casey).

The photographs within the book further the mystery, though a different sort. The women are branded, the men are bemused. Hysteria is no longer recognized as a disorder, but the idea of incurability still remains across all societies, which is why this book is so successful; in uncovering the imagined stories of these women and these real photographs, a person is moved to introspection.

The language in the book is gorgeous. For example, quotes such as “Sometimes she was a magnet and all the men little pieces of metal waiting to be drawn up” (27) and “Bodies, you think, are like haunted houses” (57) are lyrical and haunting. The voices you give to these women are equally captivating. Were there any parts of this book that were hard to write, emotionally or mentally?

The sound of this book—the different sounds each section makes—felt important to me. I wanted it to sound choral, polyphonic, affecting the reader the way music does, on a visceral level beyond words. I think that’s one of the things that interests me most about writing—the endless effort to take myself and the reader to a mysterious place beyond words with words. This material can be grim, but that I get to write about it from this distance feels so lucky; that perspective is one I always return to: the book was hard to write, but it was harder to be confined in the Salpêtrière. I wanted very much, too, to include moments that weren’t awful. Fleeting glimpses of mundane, inconsequential moments in a life, in lives; these inconsequential moments aren’t so inconsequential after all. Sometimes they are strange and wondrous, and impossible to convey in real life.

In your interview with Louisa Ermelino from Publishers Weekly, you state that you set out to write a collective consciousness. Could you expand on why?

This book grew out of my longstanding interest in the history of psychiatry, and its use of that new technology, photography, as a forensic tool for diagnosis. I first encountered Georges Didi-Huberman’s book, The Invention of Hysteria, a book about the link between the diagnosis of hysteria and photography, in college. That book includes reproductions of some of the photographs of the girls and women diagnosed with hysteria by Jean-Martin Charcot, the renowned neurologist who resurrected that diagnosis. They are haunting—staged, strange, heartbreaking.

Didi-Huberman introduced me to another haunting detail—that the women and girls needed to hold the pose to give the photographer time to change the glass plates. The photographic technology of the time meant there were seconds when, well, when what?—there was collusion, agency, collaboration, it’s hard to know what to call it. The question stayed with me. Then I had the good fortune to collaborate for many years on this project with the photographer Laura Larson. That collaboration led to two books, mine and a book of her own writing and photography (https://www.saintlucybooks.com/shop/p/city-of-incurable-women). The conversations we had about photography, specifically around the archive of the photographs at the Salpêtrière, was invaluable.

Forensic and medical photography in the 19th century was all about looking. A photograph was proof. Illness written on the body. One of fiction’s particular gifts is its ability to get underneath surfaces, beneath diagnoses. I didn’t want to suggest I had answers, and so the kaleidoscopic, ever-shifting points of view—stories in first-person, second-person, third-person, and that collective we—felt essential. I didn’t ever want to get too comfortable as a writer, and I wanted the experience of reading the book to be slightly disorienting.

And now for the more straightforward answer to your question! That collective consciousness—that we—began to take shape after Laura and I visited the Countway Medical Library at Harvard, where there is a cache of photographs of women and girls diagnosed with hysteria from the Salpêtrière. These photographs are different than the photographs of the more celebrated women/girls diagnosed with hysteria because they are, essentially, intake photographs. Bureaucratic. Heartbreakingly so. The women/girls are anonymous. They likely disappeared into the mass population of the hospital, never to be heard from again. I wanted to find a way to speak to that anonymity. Not for, so much as to. The collective perspective became a way to offer context for these anonymous lives, factual and invented, as well as fleeting glimpses of ordinary moments.

Towards the end of the book, the collective we state, “Our last words? We are still considering. We’ll let you know” (21). How would you describe the experience of resurrecting these women and giving them voices?

These lines come on the heels of Charcot’s last words, which were, allegedly, “I am feeling a little better now.” Last words are always a little suspect, but as last words go, these are pretty good, invented or not. My experience of writing toward these voices was one of stumbling around (this is a pretty good description of most of my writing). I didn’t want to resurrect these women, in part because I couldn’t. They are long gone, as are their voices. I’m not sure how to describe what I hoped to do without sounding really pretentious, so I’ll forge ahead and risk pretentiousness. I wanted to meditate in their direction (which may, actually, be a riff on a lyric from “Grease”?), speak toward them, work with the historical material to create an atmosphere that allowed me to consider the banal moments in my imagined versions of their lives alongside the oppressive system within which these women were trapped. Most of all, I wanted the book to suggest that, even within the cage of a rigged system, imagination and love, or the memory of love, can create a space, or texture, or just…something else. It might not last for long, but it exists.

I think, too, I wanted to create a sense of privacy. These women, these girls, eluded the medical men who poked and prodded and otherwise victimized them because of their gender, because of their class. These women, these girls, who experienced molestation, poverty, self-mutilation, but also, quite possibly, love and moments of wonder, elude me too. I don’t want to claim otherwise. Still, I wanted to create a structure in which I could ask questions and undo the knots of history.

I really enjoyed your New York Times article “The Museum of ‘Please Find Me.’” In this article, you discuss the human condition of losing and, more specifically, losing things at airports. Thinking about this article in tangent with your book, what do you imagine the incurable women losing at airports?

Thank you. As an expert loser, I was grateful for the opportunity to write that essay. I love this question! Part of what I love is imagining the so-called incurable women of the Salpêtrière traveling through time; that’s what I wanted to conjure, in part, the sense of time travel. Or, maybe, writing stories that created the effect of speaking from outside of time? Busting an imagined version of these women out of their historical cage? I like to think of these women leaving the ovarian compression belts in one of those trays, leaving them behind, gliding along the moving walkways, and flying business class.

You dedicate this book to “fellow incurables.” How do you imagine this book impacting women?

I’m not sure I’ve gotten as far as imagining how the book will affect women. I’m still in that place of amazement that the book is an object in the world that people are reading at all. Reading is such an intimate experience, an engagement in which the reader brings so much of themselves to the work. Your questions are evidence of that kind of engagement. That I’ve written something that other people might engage with in that deeply private, mysterious way—it’s a lucky, lucky thing. That’s mostly how I feel, and then, if my book allows people to make connections between what was going on with women and medicine in the 19th century and now, or leads them to read Ian Hacking or Asti Hustvedt (Medical Muses: Hysteria in the 19th Century Paris), and to consider the way things have and have not changed since then, that’s great too.

Incurability as a problem, as in the problem for 19th century doctors of the female body, suggests to me, too, its flip side, as in maybe incurability isn’t a problem so much as how things are. Aren’t we all incurable, as in full of desire that will never be sated? Aren’t we all mortal, and so incurable? The dedication is, in some ways, to anyone who understands incurability to be part of the human condition. To all us mortals.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

Jada Renee Ford is very short and pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Georgia State University. Her heart belongs to dangerously sweet things and Conan Gray. In addition to creating and editing a collaborative zine (Hot Propaganda), she has a poem published on pidgeonholes.com (“You’re Not That Dark”) and contributed to a Vice article (“Why Juneteenth Feels Different This Year”). Her other work can be found by visiting https://linktr.ee/jadawrites. She is an Assistant Editor at Five Points.