Review: Natasha Trethewey’s “Thrall”

by Christine Swint · October 17, 2012Coinciding with Natasha Trethewey’s appointment as the 19th Poet Laureate of the United States is the launch of her fourth collection of poetry, Thrall (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012).

In a June 7 press release from the Library of Congress announcing Trethewey’s appointment, librarian James H. Billington describes Trethewey as an “outstanding poet/historian in the mold of Robert Penn Warren, our first Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry.”

Trethewey, who has named Warren as an important poetic influence on her work, introduces her collection with an epigraph from Warren’s poem Audubon: “What is love?/ One name for it is knowledge.”

One of Trethewey’s great gifts as a writer is her ability to take her personal history and connect it to the histories and memories of a people. In a Five Points 11.3 interview published soon after her third collection, the Pulitzer Prize winning Native Guard, Southern literature scholar Pearl McHaney says to Trethewey:

You dedicate Native Guard to your mother, in memory, and the book is the elegies for your mother, the weaving together the personal and the public histories, the erasures and the monuments and the memorial. (101)

In a historically symmetrical manner, Thrall begins with “Elegy,” dedicated to her father. Because her father, poet Eric Trethewey, is still alive, the reader enters this poem as a meditation on the past and how we reconstruct our histories with language. She addresses her father, “I can tell you now that I tried to take it all in/ record it/ for an elegy I’d write–one day–” (4). The speaker admits that even in the midst of a fishing trip with her father she is thinking of the metaphorical possibilities that will later become her poem.

After this introductory elegy, the poems explore paintings and other historical documents pertaining to imperialism, and specifically, to the Casta paintings from colonial Mexico. These paintings depict a byzantine taxonomy of blood lines based on how close or how distant the subjects were from “pure” Spanish blood. Theoretically, the closer one was to Spain, the closer the relationship to the crown and by extension, to God.

“On Captivity,” which first appeared in Five Points 11.3, begins with an epigraph from the journal of Jonathan Dickinson, an English Quaker living in Jamaica who was taken captive by native people living in what is now Florida.

The first stanza again quotes from Dickinson’s journal, citing his term for his captors: “savages.” Indented cinquains wind down the page as if to imitate the hissing of this word as well as the Biblical serpent mentioned in the second stanza. The speaker questions the legitimacy of the word “savage” as the captives are stripped of their clothing, the thin veneer that distinguishes them from their captors, with only “the torn leaves of Genesis” to cover their “secret illicit hairs” (13).

“Geography” (45) and “Rotation” (55), both first published in Five Points 13.3, return the reader to the speaker’s personal history. As we progress through the collection, we understand more about the speaker’s relationship with her white father, who leaves the family in 1971, as written in “Geography.”

In each of the three parts of “Geography,” the speaker pinpoints a memory as if it were a photograph, describing the location and the circumstances surrounding a particular instance in time. But in each section, the father recedes from the daughter. The speaker characterizes him as a pretend hitchhiker, “a stranger/ passing through to somewhere else.”

Woven together with this mournful passing of their relationship are the ekphrastic interpretations of the Casta paintings. Through the juxtaposition of meditations on imperialism, the reader gains entrance into Trethewey’s personal history as well as the history of the colonies, and by extension, the emotional tenor of our contemporary times, in which we as a culture still discuss, or refuse to discuss, the effects of slavery and patriarchal, top-down histories.

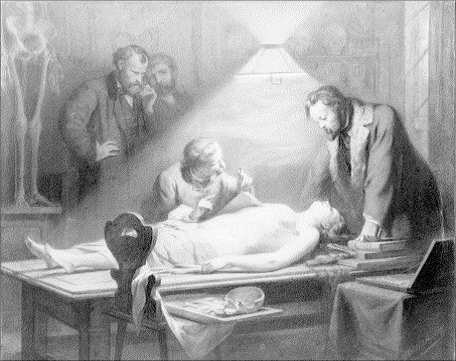

In “Knowledge,” the speaker unites the two main threads of the collection, combining an ekphrastic contemplation of an 1864 chalk drawing by J.H. Hasselhorst with a quotation from her father. The poem is an emotional description of a dissection in which the speaker identifies with the woman on the table. She exclaims, “…how easily/ the anatomist’s blade opens a place in me” (29). She goes on to reveal her father’s words about her: “I study/ my crossbreed child” (30).

In “Knowledge,” the speaker unites the two main threads of the collection, combining an ekphrastic contemplation of an 1864 chalk drawing by J.H. Hasselhorst with a quotation from her father. The poem is an emotional description of a dissection in which the speaker identifies with the woman on the table. She exclaims, “…how easily/ the anatomist’s blade opens a place in me” (29). She goes on to reveal her father’s words about her: “I study/ my crossbreed child” (30).

In an interview in Sycamore Review 24.1, Trethewey explains her process of writing “Knowledge,” stating, “I quote the line from a poem of his [her father’s], and later she says, “I’ve been hearing that poem all my life, but not until that moment did I realize why it’s always bothered me. It was both the Enlightenment thinking, and the idea of ‘crossbreed’ ” (33). In the poem, dissection becomes a metaphor for the father/daughter relationship that wounds the speaker. Like an anatomist who studies a specimen, the father has studied his daughter.

Thrall is an important book. Not only is it an example par excellence of Trethewey’s superb craftsmanship as a poet, but it also shows the relevance of poetry in how our truths are told, how important it is for poets and readers alike to re-examine the past in order to understand the present.

More Reading

For further interpretation of Thrall and more sample poems, read Elizabeth Lund’s review in The Washington Post.

Eric Trethewey’s essay “Combinations” in Five Points 12.3 is a memoir about the early years of his career, his family life, and his marriage to Natasha Trethewey’s mother Gwen.

Christine Swint is in her final year of the M.F.A program in poetry and creative writing at Georgia State University, where she also teaches first-year composition and introductory poetry writing. Her writing interests include modernism, Eastern philosophy, folktales, motherhood, and ekphrasis. Her poems have appeared most recently in Ekphrasis and Hot Metal Bridge. She is the winner of the 2012 Agnes Scott Writer’s Festival award in poetry, judged by Joy Harjo