“To Be Awake and Responsible for One’s Actions” a co-interview between JoAnne McFarland and Elaine Sexton

by 5 PTS · July 29, 2025Five Points has published the work of both McFarland and Sexton, and editor Megan Sexton (no relation to Elaine), seeing a common thread, invited the two to co-interview each other for the journal. This interview truly began as a conversation between two new friends and colleagues one evening train ride to New York City, home to both writers, following a poetry reading at the Philadelphia Free Library in April 2025, a celebration of Grid Books, a press they have in common, with fellow readers, poets Lisa Sewell and Elaine Terranova. Later, when this opportunity presented itself, the two authors discussed (via Zoom) what a “co-interview” might look like, and agreed that submitting and answering inquiries in writing gave them each the most flexibility and opportunity to ponder and best respond to a wide range of questions.

This co-interview begins with a focus on their newest published works: Sexton’s Site Specific: New & Selected Poems (Grid Books, 2025), and McFarland’s American Graphic (Green Linden Press, 2024). Because McFarland’s is the third in a trilogy: Pullman (Grid, 2023), and A Domestic Lookbook (Grid, 2024); and Sexton’s benchmark book is a new & selected (2003–2025), featuring work from four previous full-length collections, their questions begin with craft, subject matter, structure, but evolve, giving each poet and maker an opportunity to revisit the origin of their ideas, and investigate practices that evolved over several books. They share their experience of art and the impact it has in shaping their work. The title of this piece comes from a comment McFarland made in response to one of Sexton’s questions, whose own work follows a similar line of thought. Their co-interview begins with a series of Sexton’s questions, and ends with McFarland’s:

American Graphic

Elaine Sexton: American Graphic is such a unique book, to say it is a hybrid, or a collection of text and images, doesn’t really do it justice. It is made up of images of many elements that are handmade: beadwork, collage work, researched and found recipes and text and illustrations, original poetry and prose. In your life as a maker, what came first, the visual art or the writing? And in the making of this book: did one lead the other? (the image, the idea, the words…)

JoAnne McFarland: Thanks so much Elaine! I’ve always been an artist. My first memories are of just mucking around with stuff and loving it. My parents gave me an easel and set of oil paints for Christmas when I was six. I still remember how it felt to find that gift under the tree. Poetry came much later, when I was in college. I’d always loved poetry, and spent hours as a kid with my mother’s worn copy of A Child’s Garden of Verses, but I didn’t start writing poetry until I was in my twenties.

For American Graphic, there was an earlier, digital version that contained an opening section entitled “Tone Poem” which unfolded as a series of delicate color tints loosely bound together by a narrative. So right away, the collection merged my two loves—visual art and text. I think of these as interlocking modes of expression, with rules, patterns, and idiosyncrasies just like spoken languages. The “Tone Poem” only worked digitally. I came up with the Sampler and Ingredients sections as substitutes when I designed the book for print.

ES: American Graphic is so carefully composed, each time I go back to it I notice more and more. There feels like a kind of controlled burn, the distinct emotional registers start small, the images, small, and everything gets deeper and more intense as we move through the three sections: “Sampler,” “Ingredients,” and “Accounts.” In the middle section, “Ingredients,” we read: “Every woman has a tongue/Her appetite can be a death sentence”…(alongside recipes) and other zingers like: “Age is a love affair with loss….” The most powerful and heart-wrenching section has to be the third: “Accounts,” with the knock-out punch introducing the voice of slave owners, side by side with love letters and elegantly composed collages. The book itself is a collage. Could you talk about how this came together? How much was orchestrated, in advance, and how much came from that gift of collage: chance?

JM: I knew the title before anything else: American Graphic, a play on the title of the iconic painting “American Gothic” by Grant Wood. I loved how the word graphic implied visual content, as well as texts that were visceral in nature. American Graphic had no art when Green Linden Press awarded it the 2024 Wishing Jewel Prize for Poetic Innovation. The Reward Posters were the sole graphic element.

I knew right away that the modern-day accounts, those between the unidentified seekers, belonged with the Reward posters. I wanted to create a portrait of freedom. That’s what we say America is about. We claim this, but we don’t model it. I wanted to model what freedom looks like to me. There’s a place on one of the posters where the phrase is—”I will give the above reward….so that I can get her again.” What does he think he’s going to get? Because a human being cannot truly possess another human being, no matter how much they try to control them. Our relentless pursuit of beauty, youth, other people corrodes our ability to truly be free.

I wanted to create a portrait of two people in the process of stitching together their own freedom, almost making a gorgeous quilt from it. The reader learns so much about their circumstances, but incrementally. It’s exactly the way I would paint a portrait in oils: first choosing a support, then laying down the ground, then blocking in the largest shapes, then finding the shadows, and on and on. The portraits in “Accounts” unfold the same way—who these protagonists are becomes clearer and clearer. Most of all, I wanted the primary voice to belong to a woman actively in pursuit of her own pleasure, able to articulate her desire, who can make space for someone else’s needs. This is my response to the passage from the Ingredients section: “Every woman has a tongue, her appetite can be a death sentence.”

ES: Would you talk a little about the subtlest visual element (to my eye) in the book, the bright beaded fruits and vegetables, and other tiny elements and what they suggest. And maybe a bit about your practice of beading, of things that are handmade.

JM: Once I knew the collection would be published, I began imagining the art. I started doing the beaded panels as an outgrowth of earlier work with beading. I wanted them to take a long time to make, so I could really savor the process. I love doing things that are rhythmic: knitting, sewing, cutting, even painting a room—anything with soothing, repetitive motions. I built out the beaded images so they feel almost three-dimensional. Fruits and vegetables are so saturated and sensual—a perfect fit with Malinda Russell’s recipes!

I wasn’t sure if the images belonged in the “Ingredients” section; I thought they might siphon away energy from the texts. After a few months though, I had a lot of panels! Christopher Nelson, the editor of Green Linden Press, thought they added texture to the entire section, so we decided to let them braid the poems together.

I tried various approaches for “Sampler,” but liked the quilt blocks best. The dress collages in “Accounts” came at the very last minute (I know that’s hard to believe). A lot of the images in the collages come from a 1972 copy of Ebony magazine that I found at my mom’s place one afternoon. It had probably been there for decades. A few weeks after making the dress collages, I woke up thinking—I know exactly where they go!

Chris really helped putting American Graphic together. Many of the design choices regarding fonts and layouts were his. Our collaboration sustained me through the entire year of making the book.

ES: The love letters. They are so spare. We don’t know who they are addressed to, who the speaker is, who the beloved is. I love the clear-eyed tenderness found here in the prose, with what’s given and withheld, the voice is so unexpected, and exposed. Tell us a bit about why you present them this way: no salutation, no signing off.

JM: My poems are not strictly autobiographical. For instance the poems in the “Sampler” section allude to my childhood, but do not describe events as they unfolded. The texts in “Accounts” are real. They’re from a period in my past when I felt divinely free and deeply connected at the same time. Part of what “Accounts” means for me is that true freedom is so precious, so weighty in the need to be awake and responsible for one’s actions, that these moments can vanish in an instant. I didn’t want to publish both sides of the correspondence without permission, but asking the reader to intuit the missing half turns out to be even more powerful.

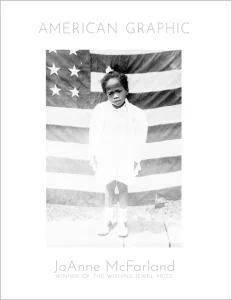

ES: We’ve spoken already about the image on the black & white cover, a photograph of a young child standing in front of an American Flag (in black & white). Would you share the story of the cover? and the various ways it has been interpreted, particularly by your editor at Green Linden?

JM: The image is of me, age three, in nursery school, the day school photos were taken. I remember that day clearly; I had been playing and fell down and hurt my mouth right before my turn with the photographer. Something about that image haunts me to this day. It’s a photograph that’s difficult to decipher while being incredibly full of signs.

I offered up alternatives to Chris, but he said, no, this is the one. When he sent me the final cover, the head area seemed even richer, and it reminded me, especially from a distance, of photos of victims of lynching, because of the head tilt and position of the arms. In an odd twist, this idea led me to my current body of work which deals with lynchings of Black women in the decades following the American Civil War.

ES: You and I have had some great conversations about our latest books, and in particular the issue all writers and makers face in sharing our work, in print: how much to explain, what to include, what to leave out? Could you talk about some of your choices (like the one I raised earlier with the portion of the book using love letters).

JM: I have tremendous faith in the ability of works of art to make themselves up. I have enough skills in my toolbox, enough ways to find things out, and an inexhaustible capacity to fall in love with everything around me. I trust my ability to sort and order material, to just play and play until something feels right. When poems arrive, I try not to change them too much. I keep opening up space for new things to exist, as they seem to want to exist. I think of my practice as a kind of stewardship. That’s what it feels like to me.

ES: American Graphic is the third book in a trilogy. At what point in the process of writing Pullman, then A Domestic Lookbook, did you imagine this third project? I know it is a big question: but was the process of putting each together very different? How are they alike, how are they different, and how do they fit together? (Choose whatever part of this question interests you!)

JM: These three recent collections all began with a short digital track entitled: Pullman: A Meditation on Loss. In the brief digital work which can be seen here: [Pullman], the moving pages reminded me of a Pullman Porter moving through a train. The day I made it, I emailed practically everyone I knew with the subject line: Breakthrough. I had been thinking about how to get my poems to move for more than a decade. I designed all three primarily as digital works composed of text, historical material, and art. The digital works still excite me the most in the way they capitalize on the unique power of modern technologies. I also wanted to create works that resist being monetized.

Part of me is sad that few people know that, as one example, in the “Field & Stream” section of the digital version of A Domestic Lookbook, each stream (for instance SALIVA or SEMEN) spells itself out, letter by letter, as the reader watches the “haiku field” in the middle of the computer screen. You can see the animation here: [Field & Stream]. I Love the print versions of these books! Pullman and A Domestic Lookbook, published by Grid Books, are the most beautiful books I could possibly imagine for this work. But the digital pieces have a magic all their own. We designed all three books with so many blank pages to compensate for the loss of the dreaminess that is inherent in the digital experience. The digital experience is more like listening to a song, a song powered by the singer’s expression and control. Audio versions of the Grid titles capture some of this feeling. My excitement around animating different sections differently—well, that’s how I ended up with three collections! I’ve preserved the digital works as part of my personal archives. The digital version of American Graphic won the 2023 Experimental Poetry Award from the Connecticut Poetry Society. That earlier version, which includes the “Tone Poem” can be viewed here: [American Graphic]

ES: What’s a day in your life of making look like? Do you write every day? Do you make something every day? What do you do to re-charge?

JM: My working philosophy is that violence and creativity are opposites. I do one creative thing everyday to thwart the relentless violence in our culture. I work best in winter and slow down a bit in summer, but I’m always working—365 days a year. I’ve engineered my living space, a clutter-free, radically safe zone, so that I can do anything I want, with as much daring and faith as I can muster. I get loads of inspiration from people who visit my live/work project space Artpoetica and share their work and ideas with me. The best way for me to recharge is to spend time with my son Stephen or daughter Lissie, or both. I’ve accepted that during this nationally and globally chaotic period, I’m just not going to sleep very much. I love my Brooklyn neighborhood. I get a huge amount of energy from just walking around, saying hi to people. I’ll probably always live in this city (although I’m always pretending I’m about to move).

ES: You’ve mentioned new work stemming from the cover image of American Graphic, can you say a little more about what’s next?

JM: I’ve begun the process of sending out my latest piece, inspired by where American Graphic left off. I’m convinced there will be a musical component; I’ve continued to think about the similarity between the digital experience and singing. This may involve a collaboration, or, I may need to invent a whole new form. We’ll see!

Site Specific: New & Selected Poems

JoAnne McFarland: Time is a central and dynamic player in so many of your poems. Words that relate to “time and the envelope it comes in” (from your poem “Figure & Ground”) populate the worlds of Site Specific. Can you say more about how awareness of time relates to both your life and practice?

Elaine Sexton: I’m tempted to answer your question with a question: isn’t all poetry in one way or another about time? The images and ideas related to time, the “envelope it comes in” is what interests me. I grew up with an awareness of the fragility of time, with the early and sudden death of my father, when I was three. A life-long practice of noticing things, recording things, appreciating tiny, overlooked things is like second-nature to me. I think of this early loss as the source of a hyper-awareness of the tangible, but also fleeting things. In my first book, “Sleuth,” the title poem is an investigation, time collapsed into all I could know or learn about my missing father “by what he collected, and read.” And gathering together the early poems in this new & selected afforded me the chance to look back and see the trajectory (and origin) of ideas I still write about, in different ways.

JM: Pushing more deeply into the way we understand time, that it’s not something we can control, or evade, I notice that many poems in Site Specific focus on how non-specific experience really is. A dominant theme throughout your collections is ambiguity, understanding that two opposing things can be true at once. The screen door that appears in several poems seems to embody the zone where much of life gets lived. Can you say more about this? Is it really “always very early morning” at this juncture, this place where you can both enter and leave? (from your poem “Screen Door”)

ES: Well, the screen door poems, and I think there are just two, are new! I started writing about and making collages with screens during the pandemic, repurposing a torn screen retrieved from a trashed door. A screen door is porous like memory. It is also a barrier, like a solid door, keeping some things out, but it allows so much more in. Literally and psychologically, it is something both closed and open, allowing us to see, hear, smell what’s on the other side, what a solid door prevents us from experiencing.

Thank you for challenging that last line: “it’s always very early morning.” It came as a surprise to me when I wrote it. I think of a screen door, among other things, as a symbol of spring something carried up from a basement (or out of storage) after a long, cold winter—a ritual. Spring, of all the seasons, does feel to me like: morning. The screen door, while closed, is also an opening, and the emotional opposite of the solid doors my mother faced in another poem, a very early one: “The World Book.”

JM: The poem “Sound + Color” leaps out from the first section of Site Specific. It conveys an absolute delight in the staccato sounds that course through the English language. The poem is percussive and jazz-like. Its colors, in particular its muted colors that “stow in the fog” remind us that “eventually, everything is shade.” When you’re creating poems, do you read them aloud as you write them? Can you say more about the acoustics of English, and how they relate to your practice? Do you speak or write in other languages?

ES: In the newer poems I’ve been leaning more and more into the sound words make, letting the literal sense slip a little, finding out what happens if I let them make more sonic sense. So maybe that’s what you’re picking up on when you say “Sound + Color” is “jazz-like.” I do read my poems out loud, when I begin to revise them. That’s a sure way to hear words that are clunkers, or just don’t land right. I should point out, that title is meant to be read: sound plus color. I used the + sign, hoping the reader’s voice, the one in her head, will say plus, instead of and. Sadly, I only speak and write in English, but I am influenced by those closest to me, my family of choice, who are French and Spanish (native) speakers. How words in these languages hang together, how they sound, how they fit or don’t fit, collide and collaborate with English, word origins and the sounds they make, pronunciation, is part of everyday conversation. So it is interesting that you think to ask.

JM: The very first poem in Site Specific refers to the speaker as “The Work of Art,” an oil, “a green that is always about to be black.” What’s the significance of these two colors? Colors have alchemical status within your poems, serving as portals into meditative states, as evidence of the passage of time, and as vessels of ambiguity. Mostly these colors derive from the natural world: blues, greens, warm reds and golds. The poem “Poetry is a Tunnel” feels important in the way it merges so many of your concerns: Time: “I imagined more time”; Potentiality: “screens (that are) alive when the light hits their surface just right”; In-between colors that convey what time does: “both head and table the color of dust.” Along with the first poem, “The Work of Art,” this poem conveys a sense of urgency around aging. Can you say more about that?

ES: Ugh. Aging. It’s unavoidable, (in poems) isn’t it? unless you are young. The first poem in the book is a kind of self-portrait, in words, drawing on Edward Hopper’s iconic painting, “Gas,” and the first time I saw myself in a painting, in my first visit to a museum. I grew up in a small town on the coast of New Hampshire, and this was my first trip to New York to stay with my eldest sister, a painter, who was living here. I vividly remember seeing myself both in the painting, and standing in front of it at the Whitney Museum for what felt like a long time. This is something that comes back in a later poem, “Evidence,” watching my “self” watching an artist at work in a gallery. I’ve come to see my experience of “Gas,” and other works of art, as self-portraiture, seeing and creating a “self” reflected in a work of art, in the act of looking. In this case in the shape of a solitary figure in a rural setting (like my hometown), alone, working at night, the dark sky, a tree-line is green going to black: the life I felt and feared to be my future. This is far away from the state, where life can be very early morning. In this painting, it is always late, green turning to black––night. I think the stunning beauty of the New England coast married to the severity of losing a parent, came together in this image of a figure on the side of the road, the suggestion of mobility, met by that of going nowhere. A few decades later I would write “Drive,” the title poem of my fourth book, illustrating the small town, mobility, volition, all subjects I often reach back to.

The poem, “Poetry is a Tunnel,” opens and closes with aging, it’s true, and moving through time, and maybe suggests the urgency you’ve pointed to. The heart of this poem is a kind of longing to be aimless. Aimlessness is something we take for granted, when we are very young, but becomes a luxury, as it costs more as we age. Time is a currency, how it is spent is more and more of a backdrop in the new poems…as the time we have left to live is clearly less than what we’ve spent on this earth so far. And what a keen observation you’ve made about the way I’ve used color to suggest not just an in-betweenness, but aging as well. And, I see now what might have spurred you to ask about whether or not I speak other languages. This poem, set in Rome, explores Italian, and that in-betweenness of a foreign language alongside color and light. I’ve spent some time writing and working in Italy, teaching in Assisi, and later working on my last book during a month-long residency in Siena, at the art institute there, and I put together the book before that, Prospect/Refuge, during a stay in France.

JM: The poem “The World Book” from your debut collection Sleuth captures the quality of restraint that powers many of your poems. There’s the line toward the middle of the poem, “Could I get more specific?” It’s not let me be more specific, or I’ll be more specific. As the poem unfolds from there, the details carry more and more emotional weight until the reader reaches the mother who is on the threshold between life and death. Do your poems serve for you as emotional containers? as record keepers? as ways of interpreting past experiences? What’s your impetus for writing?

ES: Earlier you pointed out “potentiality” in my work, and this “could I……” is an example of this. Not have I? but could I? And the “get more specific” is kind of a precursor to the title of this book: Site Specific. I wasn’t even thinking of this 20+ year old poem when I named this new collection. But of course, it makes sense that even back then, in one of my first published poems, “The World Book,” I was reaching for something abstract in the particular, in naming things, in interrogating them. But, no, I don’t really think of poems as record keepers or emotional containers, at least I wouldn’t describe them that way. Containers, yes. But more in the way the ideas themselves become a container, sort of like a sculpture, or a collage is the sum of its parts, but in your head. In the mix: ideas, experiences, observations, sounds and images, do make a third thing…the physical poem, a container.

JM: By contrast, the language in the poem “Rethinking Regret” thrusts the reader and the speaker forward into a world where risk must be embraced. It links clutter and order with regret, and warns that perfectionism may lead one to miss a world that is ready to stun with its beauty. How does your deep understanding of art, your enduring sense of the unpretentious glory of the natural world prepare you to take risks?

ES: I’m really enjoying your uncommon reading of these poems, JoAnne. This is one of my most anthologized poems, and I don’t think anyone (including me) has ever linked it to art. Or nature. And both of these I experience deeply, and write about. This poem came about after a very hard time in my life. I was able to put into words the idea of embracing our mistakes as part of being human, as markers of who we are. So rather than turn away from them, why not celebrate them for what they made possible, what could only have happened because of them. Sort of a variation of what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger. This idea of forgiveness, forgiving others, and oneself, makes a cameo appearance in one of the newest poems in this book, “Poetry.” And regarding risk: I’m not at all sure what it is that prepares me (or anyone) to take risks. I do find great solace and joy in art, seeing it, writing about it, making it. Art makes me happy. I can be in a terrible mood, and walk into a gallery or museum, and come out feeling utterly changed. And the same is true, but in different ways, with nature.

JM: For the first poem (the most beautiful thing) in the poems from your collection Drive, you repeat the phrase, “the most beautiful thing about.” Repeating a phrase within the body of a poem ties all of your collections together. When you read these poems aloud they become public incantations, with an undercurrent of contemporary urgency: [Elaine Sexton reads “Evidence”] Can you say more about how you use repetition to propel a poem and engage the reader?

ES: Thank you for noticing and appreciating the undercurrent of contemporary urgency, at least in some of these poems. As I said earlier, I’ve become more and more interested in experimenting with various sonic devices, repetition being an obvious one. Often a word or a phrase ignites an idea for a poem, and when that’s the case, I find repetition a way of drilling down, a way to find links between ideas. With the “most beautiful thing” poems, I found a device that allows me to push for the unexpected, every thing has something about it that is beautiful, but not obvious, that is particular to a person. And if you’re able to uncover it, not the obvious, but the particular, give it a name, and share it, that other thing, what’s possible, opens up the door for others to walk through, to explore and find something unique in their own experience.

JM: In “Drive” the word drive itself, an energetic word, unites many of the poems in the section. In terms of form many poems feel engineered, like roads, so that the reader travels quickly through the text. There’s an acute sense of the physical body engaged with the elements—both manmade and natural. Can you speak to how you arrived at these poems? It feels like something important got shaken loose. The poem “Copper Beech” in particular reads like an abandonment to time and desire.

ES: You’re so right about the acute sense of the body in these poems, in very different ways. “Drive,” is about being in that suspended place in a car, while driving, but also in your head: in between places. Writing this poem was a breakthrough, not unlike the way you described your breakthrough, when you found that way to “get your poems to move” together. So this poem spoke to the way so many others poems moved, had been moving, related to this idea of space, and a parallel idea of being present, but gone. “Drive” came about during a time when my brother was gravely ill and I was driving back and forth from Manhattan to my hometown in New Hampshire to see him, where he still lived––a five-hour drive. This went on for months, every week, every other week. I found myself embracing this place, this drive itself “home” to NH, and then “home” to New York. Spending so many hours in this non-place, feeling the pull from one place to the other, stirred up all the reasons one has for moving, for leaving home, for staying, and, really for making any decision at all: what drives us. Aging is here, too: “We are old,/ old enough to equate/ mobility with independence.” This poem points to the idea of volition, of ambition, of what it means to be driven, a state of both private and public transport. And, so, too, in that vein, “Copper Beach” is a poem I wrote about falling in love, not young, and both following and abandoning one’s desires, into the arms of a tree, literally accepting an invitation from the beloved to do so! Again, in the body, but leaving the body at the same time.

JM: The final poem in Site Specific from the collection Drive, is entitled “[trust]”. Archival tape holds some of Sappho’s remaining fragments in place. This lets the reader know how precious these fragments are, and how fragile. Do you see your own poems as ephemeral, or worry that they will be lost to time? What qualities in your work and/or practice have helped you build trust with an audience?

ES: These are the big questions, my friend, aren’t they? Who doesn’t want their poems to be read, and last, and to find and build an audience. But, honestly, I’m not thinking of either of these things when I sit down to write a poem. Did Sappho imagine we would be studying fragments of her poetry scratched out on papyrus centuries after she composed them? Or did she even write them down?

I’m thrilled when someone takes the time to speak to me after a reading, or when a critic takes the time to review my work. Or having this conversation with you. Just last week a stranger reached out (in an email) after reading a decades old poem “Rethinking Regret.” Someone copied, and left copies of this poem on a table in a patient support center in a hospital, and then she copied it, again, and is sending it to friends, keeping a copy on her desk. She said she gets a lump in her throat whenever she reads this poem. Which gives me a lump in my throat every time I think of her, and how she experienced this poem. [Rethinking Regret] I don’t imagine people will be reading my poems “ages and ages hence,” to quote Robert Frost. But that a stranger takes the time to write to me about a poem I wrote 25 years ago––this is enough to make me trust that writing and publishing poetry matters. This note from a stranger is one of the high points in my life as a writer. And I honestly don’t think past writing my next poem, which I hope will find a place in the world, and maybe a book. But for now I’m thrilled to be celebrating this new one of mine, and yours, with you!

All photographs were provided by the authors.