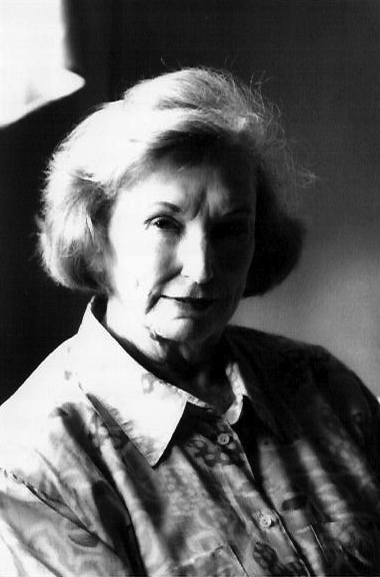

Featured Prose: Elizabeth’s Spencer’s “On the Hill”

by Megan Sexton · April 17, 2013As you all might know, Five Points Vol. 15, No. 1&2 has just been released, and one of the stories you can expect to find inside is Elizabeth Spencer’s “On the Hill.”

Here’s a little bit of info about Ms. Spencer:

Elizabeth Spencer was born and raised in Mississippi. She has lived for long periods in Italy and Canada and now lives in North Carolina. She has published nine novels including The Voice at the Back Door, The Salt Line, and The Night Travelers, plus a memoir titled Landscapes of the Heart. The latest collection of her stories, The Southern Woman (Modern Library), includes The Light in the Piazza, which was recently made into a Broadway musical.

Enjoy the story!

“On the Hill”

by Elizabeth Spencer

Regarding Barry and Jan Daugherty you first had to know that they lived out about two miles from town. Lots of people do live out in wooded areas here; the whole town is filled with trees so that the extent of it is not easily determined. Even so the Daughertys were to be thought of as distant. The little maps which accompanied their frequent invitations were faithfully followed, for they gave wonderful parties.

They had not been very long in Eltonville, only since last winter, it would seem. Exact dates of their arrival and acquisition of the property were not easily determined. The fact was nobody could pin down any exact information about the Daughertys. Jan, in fact, sometimes went by another name—Fisher. But it was easy to think she was in the modern habit of retaining her maiden name, or was it the name of a former husband? The Daughertys, if asked, gave rather round-about answers. Jan said, in regard to the name, “Oh, I keep it for Riley.” Riley was her son. Then was there a Mr. Fisher, somewhere off in her past? It was hard not to sound too inquisitive. Riley was a blonde little boy of about ten. When guests arrived, he ran about taking everybody’s coats and then vanished with them, upstairs. He reappeared at departure time, looking sleepy but holding wraps by the armload.

As for the girl, younger, probably six, she clearly was Barry’s daughter. But was she Jan’s? Were there two divorces in the background? Not unusual: who cared? It wasn’t really that anyone would care, one way or the other; it was just that nobody knew.

Going to the Daugherty house was like a progress to an estate. The road off the state highway wound through trees, but broke into the open on a final climb. The house itself sat free of all but a couple of flanking oaks. Its galleries suggested an outlook over vistas.

It was a joy to come there. How had they managed so soon to find such nice people? For a dinner invitation, you arrived just before dark and parked in an ample space. Barry himself would be just inside the door. He had a broad smile, skin that always looked lightly tanned. Sometimes a tie, sometimes not. He had picked up easily on local habits. His hair was dark brown, sprinkled with gray. He never slicked it down. And Jan? Well, she knew how to dress and how to greet. The feeling imparted was that every-thing was under control, and that the arriving guests were the choice people of the earth.

***

It would soon be dark. Looking out toward the terrace from where she sat at the end of her table, pouring coffee while Barry refilled wine glasses, Jan would say, “Last winter during the snow, what a lot of creatures wandered in.” “It happens in town, too,” one guest would offer. “I admired them, as much as you can admire a ’possum—is that it? Those things with the long snouts and skinny tails. I’d hate to dream of one. I wonder if they bite.”

“We’ll ask Riley to find out at school,” Barry said.

“They certainly bite,” one of the men volunteered, speaking from country knowledge. “But just if you corner them. They’re sort of timid.”

Where on earth were they from, not to know about ’possums?

“Then there was the raccoon,” Jan continued. “What a precious little guy. All black circles under his eyes.”

“You must have put food out.”

“Oh, just a few scraps.”

“They’ll love you to death. They’ll certainly bite you.”

Somebody had a story about a raccoon his aunt had let in the house, because he looked so cute. He had rifled the cupboards and climbed on the shelves. He had tried to get in the refrigerator. How to get rid of him?

“They carry rabies,” the same informing man said.

“Don’t disillusion me,” pled Jan.

Evenings there sped by, but when the guests spoke of them later, there was not much more to remember later than talk of ’possums and raccoons.

***

Do we really like them? Eva Rooke asked herself that, all the while observing with fascination, as they were leaving the table for the living- room, how Jan Daugherty wielded a silver candle snuffer, tapering in her slender hand, elongating her white arm where two bracelets circled.

Suppose I used a candle snuffer? Eva wondered. What would Dick say to that?

The Rookes lived nearby. It was easy to come there. Dick was with her sometimes. He could seldom be led out to parties. Eva gave excuses for him—as one of the county commissioners he often came in late and tired or had to go to some night meeting. But the true reason was his passion for music. He liked nothing better than turning up the stereo full force, four speakers blaring Le Marriage de Figaro, The Barber of Seville. Now and then something by Wagner or Massenet. He even listened to CDs of Broadway musicals—Oklahoma, South Pacific. He wasn’t choosey. Eva bought ear plugs and swore she didn’t mind. Once in the middle of gossip about local sexual affairs, how everybody wondered whose marriage would be next—she brought out that she was safe until Aida showed up. Someone who heard her caught on slow, trying to place the name.

Another truth was that people around Dick Rooke were a little timid. He was brusque with a habit of looking as if he had got himself bathed and dressed reluctantly. Everybody liked him, but found him hard to talk to. He said abrupt things. Something you had asked him five minutes before he would suddenly answer, having thought it over.

Eva, loving, knew she wouldn’t be with anybody else but Dick. They had lost one child from a miscarriage but were hoping for another.

***

Three times a week, Eva drove to her part time job in a law office, about ten miles. There was a back road she took which led through some few unexpected places—a Chinese restaurant sat out on a gravelled parking lot. A shabby old abandoned house with children’s toys scattered on the porch. And a church with an odd name—Holy Brotherhood of Jesus. Eva always looked at the building, which was plain and small with a sort of square pedestal on the roof at the right; it seemed to have been put there in expectation of a steeple. Soon they’ll raise money for the steeple, Eva thought. But then one day, in the tail of her eyes, she saw the door of the church open and Barry Daugherty came out. A man in a black suit followed and stood talking. She swerved, almost ran off the road, considered going back, decided not to, and went on her way. Perhaps she was mistaken. He had looked accustomed there, and she was sure the more she thought of it that it had been Barry. He had a certain unique quality, not easily confused with another. But Barry in a Holy Brotherhood?

***

That evening Eva told Dick about it. “Well, maybe he belongs to it,” Dick said. The church was in his section of the county and he knew about it.

“What are they like?” Eva wanted to know.

“A bunch of kooks,” said Dick, though he thought this same thing about most religions.

“How do you know?”

“Well . . . ,” he was slow to confess, “I stopped there to listen once. I sat in the back. They stand up and talk about it all.”

“What all?”

“Oh, salvation. . .Jesus. . .stuff like that. They stomp on the floor.”

“I cannot believe that Barry Daugherty is into that sort of thing. I expected they would join in with us, but they didn’t.”

“Us” was Episcopalian, the sort of religion that went with the wines and the candlelight.

Dick Rooke professed himself tired of all these dinner parties. Eva thought you had to pay people back. He helped out reluctantly when they did and Eva bit her nails, hoping things would go well. “You don’t have to do all this,” he would say, stacking wood to start a fire. She worked hard at it and was so exhausted afterwards she had to rest up for three days. But she loved those parties; everybody was so interesting. They were getting friendly with prominent people—the head of a university department, a member of the town council, a bank president. “You knew them all already,” Dick objected. But it was the setting, the way the Daughertys did things. And the sense of mystery, the sense of belonging. Eva always thought they should have more of a social life. They had simply lucked up on the Daughetrys. Dick had run into Barry in a line at the post office. They had got talking and the result was an invitation, the first.

***

Barry Daugherty answered clearly enough when asked about his vocation. He was involved in a scientific research project which might lead to breakthroughs in selected fields of cancer research. The basic work he had done at Hopkins had interested the leading research team here so they had enticed him to relocate. But where did you come from before that? Up around Philadelphia. What did you ask him next? Certainly he would answer, but what did anyone know about corrective laser surgery leading to alteration of enzyme deficiency? You switched to personal questions: Where did he meet Jan? Easy. “Skiing at Aspen. She fell and thought something was broken. Only a sprain.” He laughed. “I picked her up.”

So now, you knew everything you had asked. Could you possibly say, “What church do you go to?” Certainly, Eva’s mother, active in the altar guild, could do that. But nowadays it seemed something you didn’t ask, especially considering the Holy Brotherhood of Jesus.

She stood near a wall, looking at a three-panel picture, a natural wooded scene, each part a trifle different from the others. Barry noticed her. “It looks like Cezanne,” she remarked, fishing up art knowledge from university days. “Exactly what I thought when I bought it,” he praised her. In warming days, the guests spilled out on the back terrace. Once Eva was standing there, looking out toward a line of trees. She heard a distant thrashing sound. “What’s that?” Barry asked. She shook her head. “You’re from here,” he teased her. “You should know. Have you got bears too?” It could be, she told him, recounting a story about a bear in somebody’s backyard. Jan came out with another couple. “Don’t scare me,” she said and remarked that Eva’s dress was lovely. “You must tell me where you shop.” If she hadn’t come out, would Eva have asked Barry what church he went to? Not more about bears.

***

The time of year was leaning toward Christmas holidays. One day Eva went to the door and found little Riley Daugherty standing there in the cold.

“Riley!” she exclaimed. “What are you doing here?” She at once looked out to the drive expecting to see Jan in her grey Buick, having sent the boy with a message. But there wasn’t any car or any Jan.

“Mama’s gone away,” said Riley.

“Gone where?”

“I don’t know. I’m scared.” He was shaking, not altogether from cold.

“Come in,” said Eva. “It’s warm in here. Come on in,” she repeated when he didn’t move.

Eva gave him some hot cocoa and let him warm up.

“Why did you come to visit me?”

He looked at her steadily with large grey eyes. “Just ‘cause I wanted to.”

Eva had a feeling that was not wholly true. She told him she was about to call his mother. He only stared at her.

No one answered the call. I’d better drive there, thought Eva. “Come on,” she said to Riley. “We’ll go out to your house.” He followed.

They were up the driveway and on the flat summit within shouting distance of the house, when Eva sensed that something was wrong. “I’m going to find your mamma,” she said to Riley. “Now you just wait and we’ll come back for you.”

Riley said nothing. He continued to stare out the window.

She went toward the house with what she hoped looked like confidence, but the truth was, she was a little afraid. But why? She didn’t really know.

She reached the door. The big bronze knocker with its lion head seemed to be meeting her eye. It crashed twice. She heard nothing from within. She circled to the right and looked in on the living room where the curtains were partially drawn. There sat Jan in a large armchair, facing a younger blonde woman, who lolled in another chair. It was obvious, even without noting the glasses and half-empty whisky bottle on the low table between them, that they were both “out,” as Dick called it. Stoned.

Eva went back to the car. “Your mother’s not here,” she told Riley. “Nobody’s home. She must have sent you some message you didn’t get. Now let’s go have some ice cream, and I’ll drive you back later.”

“The car’s here,” said Riley. Had he trudged home from the school bus, then come to her? She didn’t ask.

“I expect your Dad came and now they’re off in the other car. They’ll both be back.” I’m getting good at this, she thought. But dismay was growing within.

She did take him for ice cream; then, thinking Dick would be home and tell her what to do next, she rang her house. But what could she say? Talking on her cell in the ice cream shop she was in hearing distance of Riley. She clicked off before there could be an answer. “I need to stop by my house,” she said to the boy. “Then we’ll go to yours.” So on they went.

“Isn’t it fun to ride around like this?” Eva said. Riley said nothing.

“If it was me, I’d stay out of mysteries,” Dick advised her, having listened to all of it. He had gone with her to take Riley home once again. They had found Barry Daugherty out on the lawn. He thanked them profusely, saying that all that time he had just been upstairs taking a nap. Returning, Eva puzzled on.

“But you went in the church,” she said. “You were curious too.”

“That was before we met these folks. I wonder about weird religions. I had heard some complaints.”

“But when they ring up again.”

“For dinner, you mean? Just say no.”

She sighed. She thought it was fun to go there. But she also wondered about Riley. Dick said she wondered too much. Wanting children herself, it was easy to let her mind drift toward the boy. What situation was he in? Who knew?

Then Riley showed up again.

It was an afternoon in late February, barely tinged with spring. Riley, having rung the bell to good effect, stood before the door and looked up at her. “Now, Riley, what’s the matter this time?”

“I thought maybe we could ride around,” said Riley.

It was just as far to the Daughertys’ house from the bus stop as it was to the Rookes’. She pointed that out to him. He said he knew that. “I like to ride,” said Riley.

She took a long way around. A tribe of crows sped by them, turned and circled. They looked as if they were going somewhere on purpose. “What if you could fly?” Eva asked. “I wouldn’t be a crow,” said Riley. “Let’s go away.”

Eva was astounded. “Go away where?”

“Anywhere. Up in the mountains.”

“That’s a long way.”

“Maybe the beach.”

“Don’t you want to go home?”

He thought it over. “Okay.” So she took him there.

In the Daughertys’ yard everything was quiet. The car stood there.

“Come on,” said Eva. “We’ll go in together.”

She glanced at him. He sat very still and looked ahead.

“Don’t you want to?”

Riley turned his head and pressed his face into the seat back.

Eva put out her hand to him, touched him to get his attention, saw he was crying.

“Why, Riley. What’s the matter, honey?”

“He’ll drown me.”

“Who will? Your daddy?”

Riley suddenly jumped forward, opened the door, sprang out and ran to the house. He rushed in through the front door not looking back.

***

That evening Dick was downright firm. “You leave those folks alone.”

“I’m not sure if he even said that. I thought he did.”

“There’s trouble in that house. It’s not our business.”

But now she had office work to do and thought he was right and went about her daily life. But at times she wondered if Riley might appear again and there was a catch in her heart from that very wondering. Uptown she ran into Amy Waldron who said, “Those people quit inviting us, how about you?” Eva agreed. “I think her sister’s been here,” said Amy, “but even so—.” Anyway, no more invitations. It seemed all that glow and elegance had just been phenomena of seasons past.

Despite herself, she would detour and drive past the Daughertys’ just to glance at it as it stood on the rise among trees with the front drive opening and disappearing. All was silent, and nobody seemed at home, though sometimes a car could be seen, high up.

***

Next, the truant officer. The son of some people she knew had been reported as not in school, they said, but the school couldn’t find out why. They had visited but no one was at home and so had reported the absence. “I understood you all were friends. I couldn’t find anybody.”

“If I go there and ring, they might let me in. They have a girl too, I think.”

The officer thought it over. “Try, then. But let us know.”

Dick was out. She dressed carefully and then drove there. Why did her heart beat so fast when she rang the bell?

Footsteps, then the door and there stood Jan Daugherty in an old dressing gown that could only be called a wrapper. She looked drained, tired, maybe hung over. “Oh, it’s you.”

“Why, Jan, I just stopped by to say hello. I was wondering about Riley. Someone told me he hadn’t been in school.”

“He’s sick. I’m keeping him in for a while.” Behind her the little girl was lingering palely at the foot of the stair.

“Nothing serious, I hope?”

She stepped back, half closing the door between them. “Same thing his father had. Sorry, but I need to see about. . . .

See about what she never said. Only “Thanks for coming,” and the closed door.

***

“Well then a mystery,” was all Dick would say. She had called the truant officer. He had thanked her.

“His father must have died of something or other,” she speculated.

“Will you stop all this? I never liked them anyway. Too slick and smooth. Something’s bound to be wrong.”

“It’s that church,” she pondered.

“Not our problem,” Dick said, and put on Wagner.

Seeing no more of them then, she agreed was the only right way. Still she thought of Riley. There was something about a needful child, but what did he need? She remembered the large grey eyes, asking for something. One day, well and hearty, he appeared again. She drove him home once more. He told her he wanted to go see his grandmother. He said that she lived in Hollowell, a town some miles away.

“I can’t take you,” said Eva. “Ask your mom and dad.”

“They don’t like her.”

This time, she dropped him in his driveway and left.

Long after the Daughertys had moved away, Eva found a list of Hollowell citizens but none of their name, nor Fisher either.

***

It was only a year they had been there. The house sat empty for a good while. It looked lonely. Eva was happily pregnant again. Hoping this time to succeed, she quit her job. Dick had persuaded her. In the afternoons she walked, sometimes by the Daugherty house. One afternoon in the woods across from the entrance, she saw a small boy who beckoned to her. She followed but he disappeared into the woods. She stood a few steps into the trees and called out, “Riley?” He’s looking for me.

Oh but that was absurd, she realized. The family had long gone and now the For Sale sign was down, someone else would move in.

***

It was inevitable she would go to that church. She found out the time—it was the normal Sunday eleven o’clock hour. To Dick, at home with a pile of Sunday papers, she had only said she was going to church.

She parked near some other cars and sat quietly, listening. The church windows were open to the warm day. The people who entered did not look her way. They mostly wore dark clothes, even black. She saw no one she knew. She heard murmuring that died away and a piano began to play a tune she’d never heard. Singing too, then silence. The speaking voice—a minister?—was too low to make out the words, but before long it began to rise, even to shouting, and she heard “Water? Fire? Blood?” There began a sort of chanting and a shuffling like feet moving and then a positive shout: “We consume or we will be consumed!”

Good Lord, Eva thought. She slid from the car and moved nearer to the open door. She wanted to peer inside. A man in black stood in front of the audience, waving something like a pitcher full of liquid. A line of children kneeled before him. On the table beside him, a large torch-like candle was alight. The feet began to move again, the rhythm mounting, almost stamping the floor.

The door closed in her face. A man was standing beside her.

“What are you doing?” he demanded.

“I was passing by,” she stammered. “I wanted to hear.”

“Come in if you wish,” he said sternly. “We celebrate God’s power. You can join us. But do not spy.”

“Those children,” she said. “What is happening?’

“They are souls before God.” He all but intoned. From within she heard a child’s frightened cry. She turned and hastened back to her car.

It was telling Dick about it when she got home that relieved her.

“Jesus,” he said. “I told you to stay away.”

“But you went there yourself.”

“I didn’t see them trying to kill anybody.”

“But you had heard things. You investigated.”

“Yes, I had heard things. People complained. But what are you going to do about it? The Baptists keep a lake for dunking people. Some people wash feet. Up in the mountains, they play around with snakes.”

“It ought to be stopped,” she insisted. “What did they mean by fire or by blood?”

“People just like to go crazy. Religion’s the best way. ‘Do it my way, you’ll be saved.’”

“Barry Daugherty had a scar on his face.”

“Maybe they branded him.”

They both began to laugh. She felt it had been a bad dream.

After lunch he lay down beside her. “What cold little hands.” He fondled one. “Let me warm them for you.” One of those operas, she forgot which. He sang it in the foreign words. “Se la lasci riscaldar.” She felt a thrill. His hands were warm. For the first time, the baby stirred in her womb.

***

“You ought to go to your own church,” her mother advised. She was a model in attending. “We could get all that out of you. Anyway, what do you care what they do?”

“It was the boy. He was frightened. And then the crying I heard. . . . ”

The next Sunday she did go to church. She sat by her mother and listened though did not remember later what was said, but came out feeling calm.

So now the past had dissolved everything about the Daughertys. They had vanished like a road.

***

Still, when she passed by, she looked up at the house. Then that habit too faded. She kept her appointments, doing everything as she was told, making ready for the child.

But one day, driving past on an errand, she saw at the top of the hill above the trees the high yellow lift of a crane. What on earth? She parked by the road side and began to walk slowly up the drive. The crane was in the back yard of the house, which seemed to be vacant. There were two men in the back around the crane. They looked up at her. Another man was sitting on the small back terrace where Jan Daugherty, in warm weather, had liked to serve cocktails. She could almost hear the laughter. The man rose and came to her.

“You want something?”

“Why no. . . I was just curious, that’s all.”

He looked puzzled. She felt awkward, so obviously pregnant, so intrusive on the scene.

“I—I used to know the people who lived here.”

“Well, they moved away. I bought the house.” She still stood there awkwardly. “It’s mine,” he added, as if she hadn’t heard.

“Not the last ones,” she said. “The ones before that. The Daughertys. They had children I remember.”

He laughed. “Don’t ask me.” He nodded at the crane. “Drainage problems. We’ve got to uproot the pipes. Hey, you walked here? I can drive you home.”

“No, I’m okay.” Coming closer to the house, she peered through a window, seeing the shadowy, empty space inside, as if she hadn’t believed it could be. She could glimpse the living room, even see the entrance hall if she craned. Inside, she thought something moved.

“You look here—” The voice had turned harsh. He meant business. She hastened away past the house, down the drive. At a turn a deer came out from the trees and stood still, regarding her for a long moment. I’m an intruder, she thought. The deer turned and leaped back into the wood.

Before anybody lived here, before there was even a house, the deer were here. The place was theirs. She recalled the talk about ’possums and ’coons. The bear they might have heard. Didn’t someone mention snakes? Animal life started spinning through her mind, all but clouding her vision. She sat in the car, waiting for it to clear. Inside her, the baby was stirring.

At dinner that night she told Dick, “I saw a deer.”

“They’re everywhere, especially at night.”

On the way to the hospital where he had to rush her that night, they saw no deer at all. By dawn there was another child in the world, a boy. Her mother came to stay with them. She sat and rocked and changed the diapers and Dick was nice to her.

“I prayed she would be all right,” she told him. “I asked for prayers at church.” She was a comfortable woman, wearing old-fashioned shoes that laced.

Dick had arranged for a nurse who now sat there too. There was a changing table, a bassinet. “I always pray,” the nurse said, and added, “I’m a Methodist.”

At the hospital Dick had run into one of the doctors he knew from an illness in his family. Oncology. “There was a guy here doing computer research in cancer. Daugherty. He left last year.” “They come and go,” said the doctor. “Can’t say I remember him.” He bent to a computer and found a few leads. “Seems it fell through,” was all he could report. “But I do remember now. Something about a child that died.”

Eva dozed and woke. She put out her arms and the nurse lifted the baby to lie in them. Bliss was crowding into her confusion and remembered pain. “What’s all this about Riley?” the nurse asked.

Her mother said, “She wants to name him that.”

Dick thought, looking in on the scene, three women and a baby son. He heard what they were saying. “His name’s Richard,” he clearly pronounced. “We’ll call him Rick.” I’ll teach him music, he comfortably thought. He sat down on the bed and stroked his child’s head. He took his wife’s hand.

“What’s gone is gone,” he said. “What’s real remains.”

***

So they built the wall. From back of it, came the faint echo of stamping feet, and on the hill a bear explored, a deer was watchful, and a little boy wandered, searching forever.