A.E. Stallings, a Review

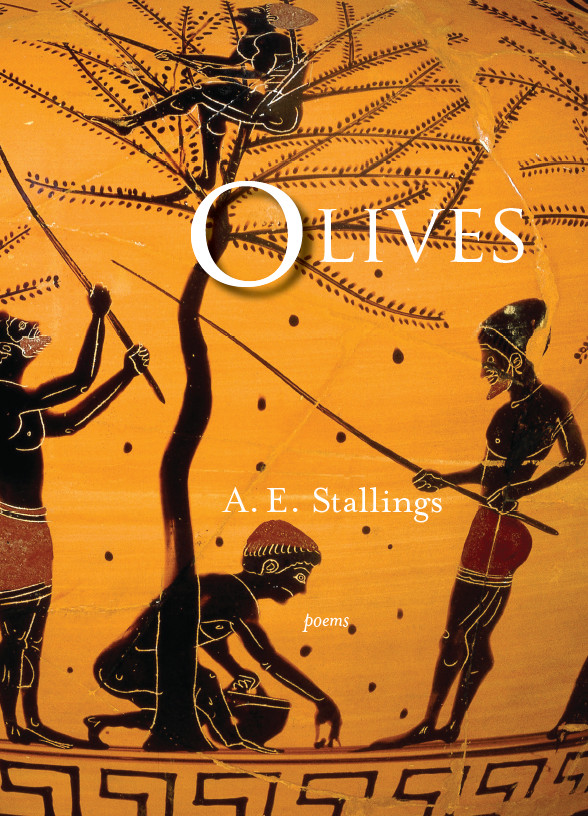

by Christine Swint · January 23, 2013A.E. Stallings, poet, translator, and classics scholar, has released her third collection of poetry, Olives (Triquarterly Books, Northwestern University Press, 2012). Her previous collections include Archaic Smile of Apollo (1999), Hapax (2006) and The Nature of Things (2007), a translation of the works of Lucretius. She has won major poetry prizes for all of her books.

Olives follows on the heels of Stallingsʼs 2011 awards: a Guggenheim Fellowship and MacArthur Foundation Fellowship.

Olives follows on the heels of Stallingsʼs 2011 awards: a Guggenheim Fellowship and MacArthur Foundation Fellowship.

In a video clip on the MacArthur Foundation website, Stallings gives the viewer a glimpse into her life as a poet and translator. She explains how she came to be involved with poetry, and she goes on to describe some of the themes she explores in her poems: love, time, mortality, and childhood.

A large part of Stallingsʼs gifts as a poet and writer stem from her ability to marry sound and form with the stuff of everyday life and myth. She writes primarily in traditional, received forms such as blank verse, sonnets and villanelles, among others.

For example, in “Triolet on a Line Apocryphally Attributed to Martin Luther” (originally published in Poetry), she playfully asks, “Why should the Devil get all the good tunes,/the booze and the neon, the Saturday nights?”

Through the three repetitions of the first line that the triolet requires, Stallings creates a wistful question that ends up equating the Devilʼs songs with an average personʼs idle singing. Any of us might “hum them to while away sad afternoons” (23). The reader is not only similar to the Devil–we also feel empathy for him.

Through the three repetitions of the first line that the triolet requires, Stallings creates a wistful question that ends up equating the Devilʼs songs with an average personʼs idle singing. Any of us might “hum them to while away sad afternoons” (23). The reader is not only similar to the Devil–we also feel empathy for him.

The current issue of Five Points (14.3) features an interview with A.E. Stallings by poet, literary scholar, and creative writing professor Beth Gylys.

At the end of the interview, referring to Olives, Gylys asks, “Are there any poem titles or poem subjects you might mention as a way of priming us for the collection itself?” (40).

Stallings gives an enlightening reply: “There are two title poems to the collection. In the one on the back of the book, I play around with the sounds and letters of Olives, which ends up containing so much.”

She goes on to say that “Olives” both as a poem and as a title for the book, is “anagrammatic” and refers to both “O Lives” and the fruit, olives (41).

In the interview, she explains that the book is about her life in Greece, where she lives with her husband, journalist John Psaropoulos and their children. The poems, ripe with imagery of the Greek countryside, explore marriage, childhood, and the land where these familial relationships unfold.

Although there are fewer poems in Olives dealing directly with myth than in Stallingsʼs previous collections, she does offer the reader “Three Poems for Psyche” (41–45), persona poems in three different voices, each persona giving Psyche advice: “The Eldest Sister to Psyche,” “The Boatman to Psyche on the River Styx,” and “Persephone to Psyche.”

As with all of Stallingsʼs poems based on myth, she is able to make the characters come alive. We feel connected to Psyche through these other voices–she gains relevance as an emblem of our own lives. We put ourselves in Persephoneʼs place when she dryly remarks to Psyche about Hades:

This place is dead–a real dive,

Weʼre past all twists, rewards, and perils.

But what the hell. We all arrive.

Here, have some pomegranate arils.

Another of Stallingsʼs gifts is her wit. Of course we feel the poignancy of Persephoneʼs plight, but the humor adds an ironic tone that makes the myth and the poem sound contemporary and fresh.

A.E. Stallingsʼs poems first in appeared in Five Points Vol. 3, No. 3, when she won the James Dickey Award for “Clean Monday” and “Airing.” As Stallings states in a note about the poem, “Clean Monday marks the beginning of Greek Orthodox Lent. Children celebrate this holiday by flying kites” (79).

Paired with this poem is “Airing,” four quatrains in which the wind causes the drying laundry to take the shape of shrugs, hugs, an argument, and then at the end, as the door slams shut, peace, the surrender of a white flag–from the start of her career, Stallings has created the magic of sound and metaphor.

For more reviews of Olives, read Abigail Deutschʼs remarks on The Poetry Foundation website or Jeremy Telmanʼs review in Valparaiso Poetry Review.