Editor Spotlight: Laura Furman, Series Editor of the Acclaimed O. Henry Prize Stories

by Megan Sexton · July 15, 2017 Megan Sexton: I was so thrilled that Kevin Barry’s story “A Cruelty” that I’d solicited for Five Points (Vol. 16, no. 3) was selected for this year’s The O.Henry Prize Stories anthology. “A Cruelty” is a powerhouse of form and culminates in a killer ending. How essential is it for a short story to render an inexorable ending?

Megan Sexton: I was so thrilled that Kevin Barry’s story “A Cruelty” that I’d solicited for Five Points (Vol. 16, no. 3) was selected for this year’s The O.Henry Prize Stories anthology. “A Cruelty” is a powerhouse of form and culminates in a killer ending. How essential is it for a short story to render an inexorable ending?

Laura Furman: For me, a story grows out of its beginning, and its ending reveals something the reader has learned but isn’t aware of yet. In that way, the word “inexorable” applies to every short story that works. In Kevin Barry’s story, we know that the protagonist is loved and protected right from the beginning. We learn that from his obedience to a set of rules constructed to keep him safe. We learn it from his careful lunch. The story develops as he copes with the world outside of home, love, and mother. We’re so connected to his carefulness and then so shattered by his vulnerability that we’ve forgotten that we know who is waiting for him at home, however ugly the rest of the world can be. So when the ending comes we’re both relieved and reminded, and made aware that no child can be protected completely. That’s the degree of involvement Kevin Barry creates in “A Cruelty.”

Megan Sexton: Over the course of the many years that you’ve served as series editor for The O. Henry Prize Stories series have your expectations for what you are looking for in a story evolved?

Laura Furman: The first collection I chose the stories for, The O. Henry Prize Stories 2003, includes “The American Embassy” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, which I found in a small Canadian magazine—she was not well known in the United States then—and the amazing “Train Dreams” by Denis Johnson, which first appeared in Paris Review in 2002 and then as a novella by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2011. It wasn’t obvious that “Train Dreams” should be included as a short story, but I knew that a story could be that big. (The story can be quite small too; I’ll point to “Deep Eddy” by Michael Parker in the The O. Henry 2014 and Christine Schutt’s “The Duchess of Albany” in The O. Henry 2007.) In that same collection there are stories by writers I’d loved for a long time, William Trevor, Joan Silber, and Alice Munro, and writers I’d never heard of before. I’m listing these diverse stories to say that I’ve never had a set of expectations or looked for a particular subject matter or technique. What I’ve always done is read until I find a story I love. I’ll do some thinking about the story for the introduction, and while writing that I often discover new things about the stories. In the years I’ve been lucky enough to edit The O. Henry Prize Stories my enjoyment has expanded at the variety and elegance of the story form at its best.

Megan Sexton: Are you ever amazed by thematic patterns that emerge between stories after you’ve paginated the anthology and gone back and read it as a whole?

Laura Furman: When I’m reading for the O. Henry, I sometimes wonder if every graduate seminar in the country is trying out the third person plural or if there’s a virus around making writers interested in junkyards or incest or whatever is popping up that year. You must see this when you’re reading for Five Points. We all live in the world and read the news, so sometimes stories are ripped from the headlines. But usually because of the time it takes for a story to be written, submitted to a magazine, and published, there’s a nice calm gap between event and story.

A superior story, of course, a really good story, could have the same theme and technique that’s abundant in a year and still stand as an individual, as unique. What I see each time I read the collection in proofs is that quality is all that counts. Subject matter is flashy and certain techniques have their moment but art lasts.

Megan Sexton: Do you feel that in recent years the story form has been modified in any way by advances in technology and social media platforms?

Laura Furman: Every shift in technology modifies art for better or for worse, just as it changes society in general. But then it settles down. Frances Kiernan, my former New Yorker editor, used to say that she could tell when a writer went from typewriter to computer. I could see that, having made such an adjustment myself. Words became more liquid, easier to put down and easier to delete. It became easier to go from draft to draft because I no longer had to face the tedium of retyping a draft to get a clean one to work on—that was the very good news for us all, editors and writers. But there are obvious costs to technological changes. The biggest one I see in terms of social media is that many young writers spend energy and time working on their presentation of self long before anyone is interested in their work or personalities or looks. Or so it seems. Since I’m not on Twitter and use Facebook mostly to try to get others to sign petitions, I’m probably not the best observer.

Megan Sexton: Do you hold out hope that ebooks, podcasts, Audible, and Netflix may help ensure the longevity of the short story ?

Laura Furman: I read the other day in the Times that this is the Golden Age of television, and that’s so if you include all streaming in the category of television. Watchers as well as readers are hungry for stories, and the need for “content” is endless. In traditional publishing, short story collections are usually published with the hope of a novel or novels to come. But the well-written or even beautiful story can be retold in many ways. So I do hold out hope that all media creators, producers, and publishers of all types will find what they’re seeking in the many short stories available to them.

Megan Sexton: As an editor and a writer have you ever felt that the “the cobbler’s children have no shoes so to speak?” How do you find a balance between these two roles?

Laura Furman: I taught until 2011, so I had nine years of teaching, editing, and writing while living in a family with a young son. (Before that, I founded and edited American Short Fiction for three years while teaching and writing.) Once I retired from teaching, everything got easier. Now my O. Henry work fulfills some law of physics—time creates work. I can’t believe that I managed to write and edit while teaching. The problem wasn’t even just time to write, it was time to dream and think, time to quit writing for the day without feeling as if I’d just given up on my last chance. Now every day is different. Some days I’ll write for a civilized two hours, and on others for seven hours. The O. Henry year of reading and then the production of the book works into the writing. In fact, it helps in some ways, bringing me into the worlds other writers create and introducing me to writers whose work I didn’t know.

Megan Sexton: Now that the new anthology is almost out—what’s in store for your own writing?

Laura Furman: In 2010, I taught in Paris for a semester. Since then, aside from one or two short stories a year, I’ve been working on a novel. As things have changed for those living in Paris, the book has changed. I’m a slow writer and a really slow novelist. It takes me a long time to find my way, but now I think I’ve got it and will soon finish it. That’s my hope. And then I want to write nothing but stories until and unless another novel takes over.

Laura Furman was born in New York, and educated in New York City public schools and at Bennington College. Her first story appeared in The New Yorker in 1976, and since then her work has appeared in Yale Review, Subtropics, Ploughshares, American Scholar, and other magazines. Her books include three collections of short stories, two novels, and a memoir. She’s the recipient of fellowships from the New York State Council on the Arts, Dobie Paisano Project, John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Series Editor of The O. Henry Prize Stories since 2002, she taught for many years at the University of Texas at Austin. Her latest collection of stories is The Mother Who Stayed.

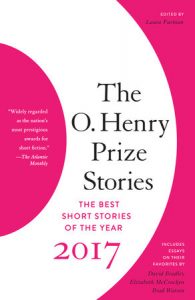

The O. Henry Prize Stories 2017 edited by Laura Furman, with essays on their favorite story by this year’s jury panel of Elizabeth McCracken, David Bradley, and Brad Watson will be out in September 2017.

BUY THE BOOK HERE

BUY THE BOOK HERE