So Much Depends Upon …Transcription

by Scott Hightower · November 16, 2017This short piece is slightly adapted from an opening comment I once composed for a family record.

"There are epochs . . . when mankind, not content with the present, longing for time's deeper layers, like the plowman, thrifts for the virgin soil of time." —Oslip Mandelstam

As a boy living on a working ranch in central Texas, I did not think much about historic family beyond my grandparents and cousins who occasional elected to visit their Texas or country “connections.” Sometimes there were photographs in letters and holiday cards. Once or twice a year, my immediate family gathered with friends and neighbors to clean and do maintenance work at our rural community cemetery. I would walk among the stones. Years later, after I had moved to New York, my mother asked me to compile some land records and family dates. By a fluke, I became far more interested in the project than it being a simple chronological arrangement of documents.

A large trove of family correspondence, a group of transliterated family letters, was given to me by Ellen Doyal, a Blauvelt cousin living in San Antonio. The trove had been the property of a mutual great-aunt, an unmarried great-aunt that we had both cherished. The narratives and some of the names of people and places lay just beyond my reach. Among them, was a letter to Aunt Cindy Miller from Samuel Langston. It was an unremarkable letter, except that is was the only Langston letter in the pack. It was posted Guka, Baxter Co., Arkansas. A quick preliminary glance through my atlas did not turn up a Guka, Arkansas. Why had a Lucy Miller letter turning up in a Blauvelt cache of letters?

An old photograph of a Sam and Lucinda Miller had hung over the mantle of the fireplace of my parent’s home. While the place we farmed and ranched carried my father’s surname as reference (“The Berley Hightower Ranch” or “The Hightower Place”), it had been referred to before as “The Trammell Place,” and before that as “The Old Miller Place.” The photograph had hung there (I thought) as historical recognition.

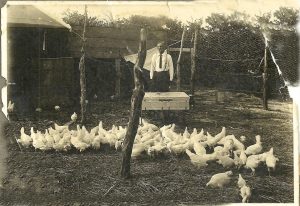

The Old Blauvelt Place—a lovely place over the hill, just off Simms Creek—was not quite as old as The Miller Place. Grandpa Daniel Bruce Blauvelt (of New York Dutch descent) had come to the county in 1876, homesteaded, married, and, with his wife, had raised seven children there. The Miller place was nestled into a mott of stately live oaks situated on a ridge near an ancient salt lick. The Millers had been in the area since as early as 1873. Both were the homes to large burgeoning families. In my mind, they were just two distinct historical family places; two distinct large burgeoning families. I knew a bit about the Miller family constellation. Veris Miller Trammell was a Miller grand-daughter: the only child of one of the Miller boys and his bride. The original house had been built by and for John Wesley Miller and Mary Rose T. Dow, his Scotts wife. Their daughter Veris Alba was born in the house at the end of their first year of marriage.” I had seen photographs and knew a bit about Uncle Jasper, Henry, Sam, and John. (“Uncle” being a country title of familiar recognition.) I knew where there had been a cabin (that always smelt of bacon and where in the summertime everyone slept outside on the porch) and a dugout. That someone raised white chickens. I knew names and a few stories . . . by connection to the place. After all, they had inhabited the spot where we now lived. All were simply landscape references without much further narrative.

I had never made any connection between the Blauvelts (my mother’s family) and the Millers.

The subject of Grandmother Blauvelt’s extended family had never been a topic of discussion. How had that one connection of Grandmother Delilah Augustine Blauvelt being one of Lucinda Miller’s eight children (the fourth) escaped me?

A short time later, I visited the beautiful Arkansas countryside around the White River near Calico Rock. This was in Izard County and census records indicated that even as far back as before the Civil War this was Langston Country. The local 1989 phone book was full of Langstons. I drove into a convenience grocery store/gas station. While paying for a tank of gas and a few other items, I engaged a local teenage girl at the cash register in the down-home kind of banter I would expect in my small home town in central Texas. No, she had never heard of Guka. A friend of hers who had come in to visit and who was clearly from an older local family stepped into the stalling conversation. She thought there use to be a little community toward Dolph or Pineville and a church named Iuka. It would be about on the Baxter/Izard County line. A typo had been curtaining off history.

After one of those “blink and you miss it” drives by Iuka and a phone call to Helen Lindley, a local historian, I drove out for a visit with Nelson “Abe” and Christabelle Langston, who introduced me to a great deal of accumulated family history: the great fire of London, all those Johns, and finally the five sons of Samuel Bennett. I was out of Absolom’s line; the line no one seemed to know anything about. Lucinda’s name had been accounted in the record . . . but nothing more of her narrative appeared. But of course, someone knew something. There had been that single letter with the mis-transcribed place name.

By tracking and cross-tracking through family news letters, “Absalom, let’s see, Lucinda and Absalom, and Absalom to Eli Barton . . .” I came up with the name Arthur Langston.

The next day, after a phone call, with time running out, I waited in the shade of a tree on a shoulder of the highway near a small local cafe. Arthur pulled up in his blue pick up, hospitably tipped his baseball cap, and we warmly shook hands. After a bite to eat and a warm visit, back outside my traveling companion snapped a photograph of us standing together in front of Arthur’s truck.

What information I was subsequently to accumulate and compile was fondly dedicated to my friend and distant relative in the blue pick up.

Scott Hightower’s “Polio and The Pleasures of Listening to Someone Reading Aloud” appears in Volume 18, no. 1.