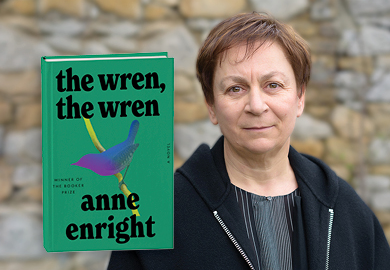

Talking with Anne Enright about The Wren, The Wren

by Megan Sexton · October 10, 2023

Anne Enright is author of seven novels. She has been awarded the Man Booker Prize, the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Irish Book Awards. She lives in Dublin.

Her recently released novel, THE WREN, THE WREN (W.W. Norton), braids together the lives of Phil McDaragh, revered Irish poet, his daughter, Carmel, and her daughter, Nell. Each woman reckons with Phil’s actions as well as his literary legacy and the toll each takes on their lives.

You are moonlighting as a poet and all the while creating a masterful story as a novelist in The Wren, The Wren. I so enjoy the intersection of poetry and fiction in the book. Did you at any time consider writing poetry when you were first staring out as a writer?

Well, I really didn’t consider it. I don’t know if moonlighting is the word because I’m imitating a poet, which is very different from being a poet. It was very fraught for me. It was quite a reach and a lot of fun because I do like a new challenge every so often in life. I had to write poetry as Phil or for Phil that would pass as real poetry, and that made me quite anxious. I didn’t realise that if you write a poem then it is a poem. I had to ask some proper, real poets is this a poem? I had serious imposter syndrome. They said, Well, if it looks like a poem, and it reads like a poem (and walks like a duck and quacks like a duck) then it is that thing, a poem. It’s hard enough to define actually, what a poem is. Phil belongs to the Irish lyric tradition. I had no problem at all with the character. His character was completely known to me as soon as I thought about it, but I had to work really hard on his formation as a poet. Most of it is dropped from the finished book—he had an extensive reading list of Irish songs and verses of the late 19th/early 20th century. Also popular editions, like Palgrave’s Treasury of Irish Verse, in there as well. There’s Patrick Kavanagh, there’s a wonderful poet called Michael Hartnett – I’ve always treasured his little book Ó Bruadair, which is a collection of old invective or curse poems translated from the Irish, just fantastic.

My real get out of jail free card was when I realized Phil could do versions of old or medieval or late 18th –19th century Irish poetry himself, so then he’s also imitating another poet: we have a sense of an original poet there. The poet-monk, St. Columba and bardic poets with verses and fragments going back to the 9th century. So that was a lot of fun. Austin Clarke is in there too—Clarke also imitated or was nourished by the bardic poets in poems like “The Lost Heifer, or the “Planter’s Daughter” There’s an absolute rip-off of “The Planter’s Daughter” in the line “the skirt she wore for Sundays” in the poem “On Killiney Hill”. This also has an echo of the Metaphyscial poets, with its ideas of circumference and foreign travel. Those owe much to John Donne and not that’s not really something you find much in Irish lyric form. That’ more me. I know that’s me.

Maybe you are a poet…

I don’t know. Those questions of self-definition—they are madly difficult, aren’t they? I know I’m a novelist. People say how do you become a writer and I say, well you write a book, and that doesn’t seem sufficient as an answer, does it? But yeah, vocationally, that’s what I have spent my life doing. Writing novels, writing short stories, writing nonfiction.

I was wondering if you could reflect on how your editor worked with you on how to integrate the poems within the book?

That’s the kind of editing I never get. I’ve been either fortunate or unfortunate that the editor takes what I give them.

Well, it’s so good, there’s not much that needs to be done.

Well, there was actually a huge amount of small work, tweaks, corrections, tiny rewrites, I am a bit of a nightmare that way. And there was some character work, some very useful character work, that happened editorially with the character of Ronan, but I don’t want to give away any secrets there. I settled on the structure maybe a year or two in, after some input from my agent, who saw the value in Nell. When I showed early pages to my husband he didn’t get the poems, and I was like what? What? So I took them out but they were just so important to me, I told him they were the whole point. The proof copy had big white pages before the poems to make them look very significant and very important and then I thought that was too much, and I pulled them back in the final version, so that would be an editorial, more sub-editorial kind of input, we worried about the white space. I wanted to give them room, but I didn’t want to make them too monumental in case they failed at that.

Do you think you’ll continue investigating hybrid methods?

Nell is already hybridizing her stuff. In Nell’s sections she has nonfiction essayistic style, when she discusses things that she sees online. So this is already hybridized, but it feels integrated and less visibly different than the poetry. And there’s a kind of difficulty and also an interest in all my work in juxtaposing different categories of writing. So in The Wren, The Wren, Nell is first-person tense; Carmen is naturalistic fiction third person past tense; it’s like they are different books already.

Are you a birder?

I’m not, no. A little wren nested in the shed in my garden this year, I couldn’t believe it I was sitting there reading and there was a little wren in an out of the bushes just at the corner of the door.

Magic…

It was just great, so I feed the birds, alright, I look at the birds. I mourn the loss of the great flocks we used to have. I think I’m not alone writing like this now.

We’re through that problematic stage. 10 years ago, if you wrote about the natural world and included the issues of climate that would have been some kind of ideological statement. But now we are through that barrier. We’re not trying to convince anybody. Now it just seems remiss not to write about it. It’s very much the way Nell thinks. It’s very much part of her mindset.

I’d love to hear about your experience studying with Angela Carter.

That was back in the spring of 1987—I was in University of East Anglia; it was a small workshop of 9 people, that was the MA class back in those days. And they were all writing fiction of different kinds. And then we had one on one meetings with Angela. 6 of them and I think I missed 2; she was away for one and I was away for another. Everyone was terrified; we walked in and there was Angela Carter, and when I went in she sort of waved at my work and said this is all fine; she didn’t say anything about it. She said, What are you going to do when you leave? What are you going to do after this? I said, I think I’ll go home to Dublin, and she said, Why? Why? She was extremely shocked. I mean Dublin was such a provincial place, in literary terms, it’s hard to remember that now because people come to Dublin to be writers, but actually that’s what London was in the old days; you went to London and pursued your ambition there.

Anyway, I said I was going back for a man and she said, Oh, all right, as if to say, If you must. She was such a presence. A little self-consciously idiosyncratic. She did me a huge favor by acknowledging that I was a writer. It was a great moment of self-definition, because there was no doubting it as far as she was concerned. That was really flattering. She came to my first ever reading, and she gave me a blurb for my book. I didn’t know that she was suffering from cancer and that she was dying basically but I think she knew. She gave me her number and said, You must to come to lunch, but I was too frightened to go to lunch with Angela Carter and I did not get back to her. That’s one of my great regrets in life.

I would have been afraid too.

Her eye was so beady. I loved the way that she flipped things. And that was a great lesson in the creative. Why don’t you go 180 degrees and see what happens? Why don’t you change the gender of the character? or Why don’t you turn the tragedy, disaster into triumph, why don’t you do it the other way around, turn the triumph into disaster? Why don’t you flip it? That’s what her fairy tales, her Bloody Chamber, did; they turned it around, and that was simply an indelible early lesson.

Nobody flips it like her.

Nobody! I think Disney should be paying her a stake 10 percent. All those heroines.

That’s true…can you talk about what you’re working on now?

I’m working on several interviews. The schedule. I’m literarily working on the schedule. I’m getting the book out. I’ll have an answer to that in a couple of weeks’ time.

How long did it take you from start to finish with The Wren, the Wren. Was it typical of your other projects?

It was atypical of I usually do.

Then there was covid…

Somebody told me once, and it was wise, that you need a year after publication before you start a new book. That was more or less how it used to happen for me. You are faithful to the novel while it’s in the public realm, until the resonance has died away, you’re still slightly with that book. But covid came and the bookshops closed and that is when The Wren, The Wren started, just a month or two after the publication of Actress. For me, that was quite a fast turnover, just three and a half years between books, very fast for me.

Weirdly, those days when the market and the readership disappeared made me feel like I was like in my twenties again – nobody was ever going to read this, I could just write whatever came to mind. And that felt rejuvenating. It was hard to think how to finish a book during the pandemic; it wasn’t a completely productive time, but it was nice to return to that privacy, when nobody cared what you did. I might as well flip it into a solution, and do whatever comes to mind.

You did flip it.

We all had to make do somehow, didn’t we? And here we are.

Able to talk about it in the past.

Just about.

(Author Photo by Hugh Chaloner)