“The Future Once”: Exploring Alienation and Elegy in Tracy K. Smith’s LIFE ON MARS

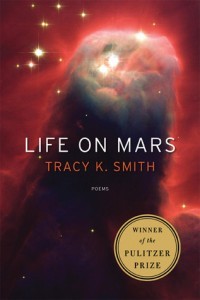

by Andrea Rogers · March 10, 2015 A few years ago, as I read Tracy K. Smith’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Life On Mars, I began to wonder why it affected me as it did, and why it obviously affected the Pulitzer Prize judges, who praised Smith’s ability to “[take] readers into the universe and [move] them to an authentic mix of joy and pain,” in the same way. As I attempted to examine Smith’s toolbox, so to speak, it occurred to me that one requirement for contemporary poetry is that it move us and connect with us in a way that we have generally come to expect from popular song. Close examination of both contemporary poetry and music indicates the necessity of connecting with audiences by appearing simultaneously private and accessible; this idea is perhaps most clearly illustrated by the fact that pop music must remain applicable for a variety of audiences, who must be able to imagine themselves as the protagonists of the songs’ actions or narratives in order to identify with the speaker in question. It appears, then, that Smith is able to connect with her audience in the same way pop music does as a result of two choices: her selection of space as a unifying concept, and her collage-like approach, which results in the interweaving of cultural icons and images throughout the poems. These choices make the collection appear simultaneously expansive and specific, familiar and alien, and, most importantly, accessible and private.

A few years ago, as I read Tracy K. Smith’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Life On Mars, I began to wonder why it affected me as it did, and why it obviously affected the Pulitzer Prize judges, who praised Smith’s ability to “[take] readers into the universe and [move] them to an authentic mix of joy and pain,” in the same way. As I attempted to examine Smith’s toolbox, so to speak, it occurred to me that one requirement for contemporary poetry is that it move us and connect with us in a way that we have generally come to expect from popular song. Close examination of both contemporary poetry and music indicates the necessity of connecting with audiences by appearing simultaneously private and accessible; this idea is perhaps most clearly illustrated by the fact that pop music must remain applicable for a variety of audiences, who must be able to imagine themselves as the protagonists of the songs’ actions or narratives in order to identify with the speaker in question. It appears, then, that Smith is able to connect with her audience in the same way pop music does as a result of two choices: her selection of space as a unifying concept, and her collage-like approach, which results in the interweaving of cultural icons and images throughout the poems. These choices make the collection appear simultaneously expansive and specific, familiar and alien, and, most importantly, accessible and private.

Smith’s selection of space as a unifying theme is notable for several reasons: first, it is most probably the result of the recent death of her father, who worked on the Hubble Space Telescope. Second, while the book takes its name from the David Bowie song “Life On Mars?,” Smith’s alteration of the original punctuation noticeably alters the meaning: the phrase becomes a declaration rather than a question, suggesting that alien life is a fact, rather than a remote possibility. Further, the poems insinuate that the idea of “alien life” is not solely relegated to alternative races of sci-fi worthy space creatures; instead, it is often our human lives, and the lives and actions of those around us, that become truly alien. Finally, and most importantly, the use of space as an organizing principle allows for a deep and sustained meditation on the multiplicitous nature of the term, the applications for which are almost endless. Consequently, in the same collection, Smith is able to examine a variety of disparate topics, including but not limited to: space exploration and the vastness of the essentially unknowable universe; the concept of physical space between bodies, both human and astral; the relationship between astral bodies and the afterlife; and the concept of liminal space, which is explored in conjunction with the unknowability of life in general, especially as it pertains to the universal experiences of death and grieving. Therefore, the broad applications of the terms space and alien allow for any reader to connect with the poems on some level, regardless of their personal experiences.

Smith’s collage-like approach is also notable, as it allows for the incorporation of a variety of images, quotes, and ideas from pop culture as they pertain to her chosen subject matter. Several of the poems take their titles and characters from Bowie songs, including “Savior Machine” and “Don’t You Wonder, Sometimes?,” which includes an appearance from Ziggy Stardust. The poems also reference several films and characters which focus on outer space: “My God, It’s Full of Stars” takes its name from a line in Peter Hyams’s 2001, mentions Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, and includes an appearance by Charlton Heston, who becomes a stand-in for a bygone era, desperately peddling an outdated model of the future. He refers to this outdated model as “the future once… Before the world went upside down,” which is similar to the Paul Valéry quote Smith employs on the following page: “The future isn’t what it used to be.” The concept of outdated visions of the future is poignant; the notion of “the future once,” or the future that “used to be,” indicates that the future we once imagined has been changed by a catastrophic or unexpected event (in Smith’s case, most likely the death of her father). Thus, notions of space exploration are layered with notions of liminal space, as Smith conflates the complex idea of “the future once” with images from both the present and the past; some, like the image of her father smoking a pipe in the late 1950s, are personal, while others are associated with cultural figures and events which most contemporary American readers can recall with ease. Further, through the inclusion of familiar cultural events, and, in particular, violent and inhuman acts – such as murders committed during hate crimes and the torture of prisoners during the Iraq war – Smith continues to tease out ideas about what is truly alien in this life.

As is illustrated by Smith’s use of space and the alien, images of the universe and ideas about universality hold the collection together. As one might imagine, death is also a prominent theme, as one such universality is the experience of grief, which has caused humans to lament, elegize, and memorialize for centuries. And yet, while grief is human, grieving often causes a sense of alienation which leads the mourner to feel separated, sequestered, or even quarantined from the rest of the world. Perhaps this is the reason Smith focuses so closely on the notion of aliens: wondering about life on other planets is similar to wondering about the afterlife. It is easy to identify the pervasive sense of loss and longing in these poems, not only for the speaker’s father, but for a time that has been forever lost to all of us, “the future once.” This future, beyond reach, unattainable, becomes an elegy unto itself, a black hole swallowing its own possibility. Smith’s poems, in their hesitant acceptance of the present and their attempts to reconcile an inaccessible past (and the future as it once was), are reminiscent of Rilke’s song-like Duino Elegies. Like Rilke, Smith honors an overwhelming and complete sense of loss while remaining cognizant of the fact that all of our deepest loves, all our knowledge, all our experiences on earth are, finally, mutable; the persistent song of Smith’s poetry, then, is what makes it both accessible and affective – because it is the melody of the human condition. Throughout Life on Mars, it becomes apparent that, whether it is a way of life or a human being, any and every subject of elegy is eventually conceptualized through the universal experience of grieving. As Rilke asserts in his “Ninth Elegy,” “even the cry of grief decides on pure form, serves as a thing, or dies into a thing.” In Life on Mars, it manages to do all three.